Artists and Dreams

We are constantly giving meaning to a torrent of impressions that we meet through our senses and from within us. We give form to raw experience. We scan our enormous wealth of words, phrases, context, to arrive at an understanding of what is communicated verbally or in writing. If we could watch this process taking place, we would observe a constant searching and rejection of non-hits, a lining up of possibilities, and a bringing to the forefront of what we sense are highest probabilities.

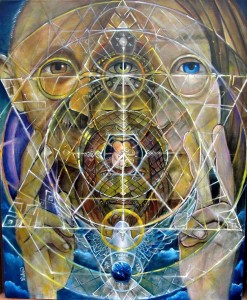

Our mind/brain is a flashing loom of connections, a constantly moving wonderful network of links between billions of cells. This flashing creative network that constitutes the miraculous background to our responses, our feelings, our thoughts and spontaneous fantasies and dreams, is constantly forming patterns from the multitude of experiences we have. It constantly tries to match these patterns against what is already known or learnt. It draws out from the chaos of memory and incoming experience whatever it can liken to what was met in the past. What it can’t match it tries to put into some sort of order or to give a form to. And within all this constant activity the search for personal meaning goes on – Who or what am I? How can I survive? Is there a way ….?

Out of such a profoundly integral search for meaning, as artist, writer, musician, we may project the subtle forms of our inner meanings into the art form we use. We may create shapes, places, people, and feelings. Out of the flashing web of our own sentience we create life – our life – with its own conceptions of what it is to exist, what it is to love or hate, to strive or fail.

Even the most modern of dream theories agree that it is out of the fathomless depths of our drive to give meaning to impressions, that we create dreams. It is out of the barely formed impressions and understanding of the dreaming impulse that we create and live. In fact many artists of every discipline – and I now use the word to include musicians, painters, writers and architects – have directly drawn from their dream life.

What we cannot quite grasp – what is too vast and many sided for us to hold entirely in our thoughts, we give form to in paintings, in carvings, in sound, in piling rocks one upon another to form a monument. We may then venerate or hold as of immense value such art forms. They hold in them for us the vast dimension of the ungraspable, of the infinity of our own within. They stand before us as represent a journey of lives of the alien in our midst, in ourselves. They remind us of what we are not masters of, and what may take hold of our life. See

In writing about Symbolism In The Visual Arts, (Page 255 in Man And His Symbols, Jung)

Aniela Jaffe mentions the drawing of Klee, interestingly called The Limits of Understanding, which expresses this attempt to put into form what cannot be thought. Jung said that a true symbol appears only when there is a need to express what thought cannot think or what is only divined or felt.

The great artists of any culture give to us what we may have failed to see ourselves. They portray to us the spirit of our times, and our predicament, and perhaps even a passage through the dilemmas we face. Sometimes they manage to break through the cultural plethora and froth of everyday life and display an insight into the fundamental forces of life, renewing our own connection. To do this they face a personal death into the unconscious. They experience darkness and light that many of us may not dare to face. They live within the great forces of their dreams more intensely, more fully than those of us whose awareness is centred on the everyday surface produced by the concepts of life generally agreed upon.

When an artist manages to meet and give birth to one of the spirits of our age, whether it is a terrible demon of our times, or a healing angel, it speaks to us beyond our reasoning. It draws crowds, it holds attention. In the early part of this century the artist Kandinsky wrote that ‘The art of today embodies the spiritual matured to the point of revelation.

Something that we must recognise as an enormous shift in human awareness that has taken place in our own times, and which must influence art from here forwards, is the attainment of self-awareness we have been helped toward by the findings of modern psychotherapeutic schools. This form of self examination has enabled us to explore the wealth of pain and wonder usually forgotten in the mists of childhood. But it also lays bare the struggle, the enormity of the evolutionary movement toward consciousness, toward being human. And there is tremendous art here when it is discovered; art expressing the meeting between the social individual we try to be, and the animal we are still largely immersed in within the depths of our mind and body. In fact we are the whole spectrum of things from sub-atomic particles, through molecular survival and interactions, on into the basic living organisms and creatures up through the lizard, the mammal and the human. All these things are active in us, in harmony, in conflict, in process of becoming. Out of this weaving loom of life all art and music arise; all life experiences an expression of it.

As an example, Thomas De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium Eater describes his fantastic dream life over a period of years. De Quincey started to take opium as a sedative. It led to a heightened awareness of how the mind can produce powerful images and memories. He writes that ‘In the middle of 1817, this faculty became increasingly distressing to me.’ Not only did his inner visions present ‘… nightly spectacles of more than earthly splendour.’ But also ‘…. vast processions moved along continually in mournful pomp. Concurrently with this, a corresponding change took place in my dreams; a theatre seemed suddenly opened and lighted within my brain.’ Such experiences led De Quincey to feel ‘deep-seated anxiety and funereal melancholy.’ At times he might recall the ‘minutest incidents of childhood, or forgotten scenes of later years, were often revived.’ ‘I could not be said to recollect them; for, if I had been told of them waking, I should not have been able to acknowledge them as parts of my past experience.’ In his visionary state however, he says ‘I recognised them instantaneously . . . I feel assured that there is no such thing as an ultimate forgetting.’

One cannot of course limit the definition of art and dreams to that of dealing with hidden neurosis, or even of the move toward wholeness. Therefore it is interesting to remember some of the artists who directly used dreams as part of their work. William Blake for instance purposefully made use of dreams not only as sources for his art, but also for invention – his method of printing for instance. He particularly tells of the man who taught him painting in his dreams. Blake actually drew the face of this character.

In the 1950’s the painter Jasper Johns was working as a window dresser in New York. In a dream he saw himself painting an American flag. In waking he painted the flag from his vision of it in the dream. The painting became a powerful force in an American revolution in art.

Salvador Dali consistently used dreams as a basis for his paintings. He tried to preserve his dream imagery in his art, and particularly to portray the subtleties of time and space. He referred to his paintings as ‘hand painted dream photographs.’

A number of film directors also used their dreams in the art. Ingmar Bergman tried to portray episodes from his dreams as accurately as possible. He felt that dreams have the ability to help people find points of connection, to link people. Carlos Saura used fragments from his dreams to capture atmosphere and environment.

For each of us, our dreams are our own studio in which we nightly create beyond our waking talent to produce the new, the novel, the unexpected and the deeply true. We are each visionaries, artists of the night and live in another dimension than that of the body. See: archetype of the artist; compensation theory; creativity and problem solving; hallucinations and hallucinogens; hallucinations and visions.

Comments

Does this also work for illustrations in a dream?