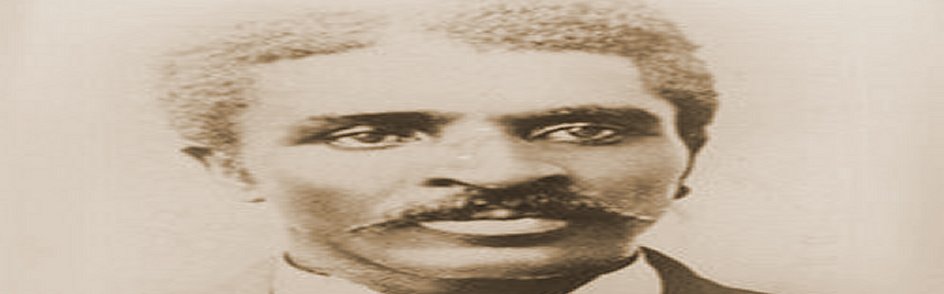

George Washington Carver

Dr Carver was not born great in the sense of family or opportunity. His mother was a coloured slave on a Missouri plantation. While still a tiny baby, slave raiders rode down on the farm and carried off the mother and child. Moses Carver, the owner of the plantation, rode in pursuit all the way to Arkansas. The baby was eventually found, and returned in exchange for a horse. The mother was never heard of again.

Being a sickly child, he was given light housework to do, and allowed much time to wander along the path of his own interests. For some time he was not named. Eventually, however, he was called George Washington because of his characteristic of telling the truth. He was also given the name of Carver for want of another.

During the many leisure hours of his childhood, George wandered in the woods, drawn to all the plants and creatures he met there. Without any formal education he began to show many remarkable talents. The plant life of the woods was drawn and sketched. He became a fine cook and householder. He also had secretly established in the woods a small botanical garden, where he had collected many curious plants. Through the ability he showed in healing these plants of diseases or insect pests, he soon became known as the ‘plant doctor.’ This remained with him to the end of his life, people sending sick plants to him from enormous distances for his help.

Music and painting also came naturally to him, but the Carvers had no money to spend on his education. Finding an old blue speller, however, he spent hours with this learning to read, this being his only source of education until he was ten. At this age he discovered a log school in a nearby town, and working at chores and odd jobs, he attended. For one year he slept wherever he could find a sheltered spot, but at the end of that time had learnt all that the teacher could offer.

Still seeking education, for something now seemed to drive him on relentlessly, he moved to Fort Scott in Kansas. Here he washed dishes, laundered, cooked, kept house, to earn his keep for seven years while he worked his way through high school. Still pushed on by his drive for education, and having received the high school diploma, he wondered where to go next. All the southern colleges were closed to Negroes and having saved his rail fare because of an offered scholarship in a northern university, he was again disappointed on arrival—they also refused ‘coloureds’. Eventually he was accepted at Simpson College, and received his Bachelors Degree in Science at Iowa State College. In 1896 he received his Master’s Degree.

Although he was then given a faculty at Ames, in charge of the bacteriological laboratory, greenhouse and systematic botany, his life work was still awaiting him. This began with a call back south to Tuskegee. It was here, with little salary, no equipment and in barren surroundings, that he became known as a saint and scientist—the “Man who Talks with Flowers.”

The American South was at that time a devastated place. For years the farmers had continually planted cotton, until now, with boll weevils and impoverished soil and soul, many farmers attempted to keep their families on about $300 a year. Seeing all this as his train carried him south, Dr Carver felt a spiritual inrush of purpose. Here was the task his whole ambitious drive had been leading to—the regeneration of the south that had rejected him. Also in the preceding years, as the flowering of his energy carried him through the difficulties of education, something else had opened in him. He had learnt how to pray.

Because of this, when he began his task of re-educating the South and travelled out with a mule and cart laden with plants and seeds, he gave more, much more, than agricultural information. Preaching crop rotation, and the planting of peanuts and sweet potatoes, he gradually led the way to rich fields and crops again, along with new spiritual harvests. Jim Hardwick, talking about one of these lectures says, “One day he came to the town where I lived and gave an address on his discoveries of the peanut. I went to the lecture expecting to learn about science and came away knowing more about prayer than I had ever learned in the theological schools. And to cap the climax, when the old gentleman was leaving the hall he turned to me, where I stood transfixed and inspired, and said, “I want you to be one of my boys!”

But Jim Hardwick had come from Southern parents, whose family had owned slaves. He says, “For a ‘nigger’ to assume the right of adopting me into his family—even his spiritual family, as in this case—was brazen effrontery to my pride. I recoiled from it.” It took Jim several days of wrestling with this inbuilt pride before this barrier fell away, and he shared the inner life of Dr Carver. To quote him again, when that happened, “instantly it seemed that his spirit filled that room. . . . A peace entered me, and my problems fell away.”

However, a climax came in his work that extended it beyond the bounds of any expectation. So successful were his efforts and agricultural reform, that farm after farm hearkened. The soil change and crop production spoke for themselves, until one year the harvest of peanuts and sweet potatoes were so big, the market could not absorb them. Shocked at this outcome of his work, and seeing the threat of a disaster, he went into his laboratory to pray. He did not ask for government aid, or demands to stop planting. In his own words, “I went into my laboratory and said ‘Dear Mr Creator, please tell me what the universe was made for?’ The Creator answered, ‘You want to know too much for that little mind of yours. Ask for something more your size.’

“Then I asked, ‘Dear Mr Creator, tell me what man was made for?’ Again the great Creator replied, ‘Little man, you are still asking too much. Cut down the extent of your request, and improve the intent.’”

“So then I asked, ‘Please, Mr Creator, will you tell me why the peanut was made?’”

“‘That’s better, but even then it’s infinite. What do you want to know about the peanut?’”

“‘Mr Creator, can I make milk out of the peanut?’”

“‘What kind of milk do you want, good Jersey milk or just plain boarding-house milk?’”

“‘Good Jersey milk.’”

“And then the great Creator taught me how to take the peanut apart and put it together again.”

The result was that for days and nights he locked himself in his laboratory. When he emerged he knew God and he had solved the problem. From that event came face powders, printers ink, butter, shampoo, creosote, vinegar, dandruff cure, instant coffee, dyes, rubberoid compound, soaps, wood stains, and hundreds of uses for the peanut and sweet potato. Dr Carver said that, “The great Creator gave us three kingdoms, the animal, vegetable and mineral. Now he has added a fourth, the synthetic kingdom.”

So what were this man’s secrets? Maybe his own words will explain once more. For on being asked how he talked with flowers he said, “When I touch that flower, I am not merely touching that flower. I am touching infinity.” He also said, “You have to love it enough. Anything will give up its secrets if you love it enough. Not only have I found that when I talk to the little flower or to the peanut they will give up their secrets, but I have found that when I silently commune with people they give up their secrets also—if you love them enough.”

See Wikipedia entry on George; The Story of George Washington Carver.

Return to Chapter Links – Go to Chapter Fifteen