Difference Between the Male and Female War Poets

How and in what ways does the choice of subject matter differ between the male and female war poets studied?

Texts Used:

Reilly, Catherine – editor. Scars Upon My Heart. Published by Virago. 1981. ISBN 0-86068-226-9.

Rycroft, Charles. Anxiety and Neurosis. Penguin Books. 1968.

Silkin, Jon – editor. The Penguin Book of First World War. Published by Penguin Books. 1981. ISBN 0-14-018367-1.

If one takes literally the question of difference in subject matter between male and female Great War poets, in a general sense there is no difference. All the poems are about the war and its influence on the writer’s or other people’s life. Apart from this a global division can only be seen when we look at the attitudes and particulars inherent in the texts. From this viewpoint, the enormous divide in social and personal standpoint between the genders becomes almost immediately apparent. This division in social attitudes between the genders highlights the major divergence in subject matter between the men and women poets. The difference then becomes obvious and understandable.

This point is made in many of the poems, particularly where women write as if they are men. In ‘Lament On The Demobilised’ Vera Brittain writes from this perspective when she says, “And we came home and found They had achieved”. She is thus placing herself in the role of one of the returning soldiers, imagining, or commenting on, how she imagined it would be. Lucy Whitmell does the same in ‘Christ in Flanders’ – “But we were ordinary men. And there were always other things to think of”. Such statements accentuate the fact that women were not as a group in active participation, so can only imagine what this would be like.

The polarity I am referring to regarding women is not simply the fact they did not take part in active combat, but that they lived within a social attitude which accepted women had a ‘place’ in the home, away from battlefields. If we define ‘place’ it refers in general to not going to work – not taking part in the brutality of war – not having the temperament, body or brain to do this. I had a memorable experience of this in connection with a very clever older man I admired in my youth. I took my first girfriend to meet him, wanting to show him off to her. No sooner had we entered his dwelling than he hurriedly pulled me to one side and explained that “Women have much smaller brains than men, and can never be your equal.”

The polarity in regard to the men existed in expectations to take part in bloody warfare – expectations to be the breadwinner for the woman and family – to be strong and impervious to many pains and hardships – to not cry or be ‘like a woman’.

Both these polarities of expectation – unconscious as it may have been for many – are implicit in most of the poems. I believe this implicit differece in these standpoints is one of the major departures in the male and female poems. It presents itself in virtually every poem. Some clear examples of this are seen in such lines as – “A child – so wasted and so white, He told a lie to get his way, To march, a man with men, and fight While other boys are still at play.” Written by Eva Dobell in her poem ‘Pluck’, this is a clear description of the drive which led this boy to join the war so he might appear a man and live out the polarity of manhood as it appeared necessary at that time. In a man’s poem, ‘Lamentations’, by Siegfried Sassoon, a similar clear attitude about how a male should be is described, in this case relating to the expression of grief:

I found him in the guardroom at the Base.

From the blind darkness I had heard his crying

And blundered in. With puzzled, patient face

A sergeant watched him; it was no good trying

To stop it; for he howled and beat his chest.

And, all because his brother had gone west,

Raved at the bleeding war; his rampant grief

The telling lines are at the end where Sassoon says, ” In my belief Such men have lost all patriotic feeling.”

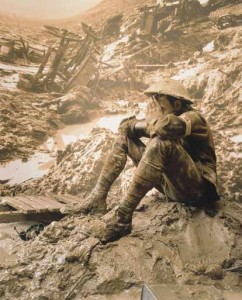

There are of course many degrees of difference within this polarising, and no absolute division. It is interesting to look at the extremes though. For the men, Wilfred Owen describes this devastating front line combat in ‘Dulce Et Decorum Est’ –

“Gas! Gas! Quick, boys! – An ecstasy of fumbling, Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time; But someone still was yelling out and stumbling, And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime… Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light, As under a green sea, I saw him drowning. In all my dreams, before my helpless sight, He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.”

Considering the number of men whose mind was snapped like brittle glass the need to fear madness was very real. There is a touching scene described where, after the extreme terror of being shelled and seeing all his nearby comrades dead, the soldier sees mice crawl out of the debris undisturbed, and clings to sanity through their unconcern – “And while I squeak and gibber over you these Calmed me, on these depended my salvation.”

From the woman’s polarity, an extreme is seen in Mary Gabrielle Collins ‘The Munition Factory’. She writes of women and the war, “Their hands should minister unto the flame of life, Their fingers guide The rosy teat, swelling with milk, To the eager mouth of the suckling babe ” A very different sentiment is expressed by Cicely Hamilton, one not found in any of the male poems. It therefore stands at this far end of the polarity. She says, “With aimless hands, and mouth that must be fed, I wait and stand aside.” This sense of not being able to participate was not something shared by men unless they were physically disabled in some way.

Less extreme differences of subject are seen in women’s treatment of lost men they loved, perhaps as a brother or husband. These frequently say how the writers experience a huge absence and diminishing of the abilty to enjoy life. Such is said in the Vera Brittain poem, ‘Perhaps’ – ” Perhaps the golden meadows at my feet Will make the sunny hours of Spring seem gay, And I shall find the white May blossoms sweet, Though You have passed away.”

Nowhere can I find in the male poets any mention of the death of a sexual partner, though there are of course plenty of mentions of the death of comrades or of their own personal death. So although death is a shared topic, there is at least this area of major difference in regard to a sexual partner. This must have been very different in the Second World War.

|

Something that is shared by both sexes, but with a subtle difference, is the strange contrast between nature and explosive warfare. “The howitzer with huge ping-bang |

Racked the light hut; as thus he broke The death-news, bright the skylarks sang” Comparing this with Muriel E Graham’s – “A lark poured from the cloud Its throbbing dreams. It sang – and pain and death were passing shows – So glad and strong” – the difference is between death and hope.

Possibly the greatest diversity of all appears only once though, and that in a woman’s poem. Writes about how good the war is for her. She says, “I drive out in taxis, Do theatres in style. And this is my verdict – It is jolly worth while.” Her subject is the high wage she gets in a munitions factory, and how it has completely altered her life.

Jon Silkin and David McDuff, in their note to the second edition of The Penguin Book Of First World War Poetry, mention the experience of war as a “shaking of foundations”, a “shock which had to be absorbed if a culture were to survive”. This is a powerful statement, and my reading of the poems certainly presents them to me as one of the ways writers and readers managed to find a way through disruption, terror, fear, and a confrontation that questioned ideals and established attitudes. But Silkin and McDuff are talking about ‘a culture’, and my impression is that the poems were often ways of dealing with very personal experiences or questions. The personal dimension of the poems explains the different subject matter chosen by the female and male poets. Rycroft says that men who were suffering from shell shock were helped when they could put the event in front of them, at a distance so to speak. They could then feel more in control of it and examine it. Poetry certainly has something of this, but it is also a communication, sharing the worst and the best. The differences in subject matter in particular, remind us in the end of how not only the sexes, but individuals, stand in various stances to even the most primitive of life experiences. Even so, it seems obvious that many of the differences were culturally created through unconscious or social expectations regarding what it meant to be male or female.

Bibliography

Reilly, Catherine – editor. Scars Upon My Heart. Published by Virago. 1981. ISBN 0-86068-226-9.

Rycroft, Charles. Anxiety and Neurosis. Penguin Books. 1968.

Silkin, Jon – editor. The Penguin Book Of First World War. Published by Penguin Books. 1981. ISBN 0-14-018367-1.

Footnotes

The Penguin Book Of First World War Poetry Edited and with an Introduction by Jon Silkin. Published by Penguin Books. 1981. ISBN 0-14-018367-1.

Scars Upon My Heart Selected by Catherine Reilly. Published by Virago. 1981. ISBN 0-86068-226-9.

Scars Upon My Heart – page 14.

Scars Upon My Heart – page 127.

Scars Upon My Heart – page 31

The Penguin Book Of First World War Poetry page 131

The Penguin Book Of First World War Poetry page 183

Mental Cases, The Penguin Book Of First World War Poetry page 195

Repression of War Experiences, Siegfried Sassoon, The Penguin Book Of First World War Poetry page 133

Rycroft, Charles. Anxiety and Neurosis. Penguin Books. 1968. Rycroft describes the effects of shell shock and combat trauma.

Edmund Blunden in Third Ypres, The Penguin Book Of First World War Poetry page 109

Non-Combatant – Scars Upon My Heart, page 46

Scars Upon My Heart page 14

Edmund Blunden, Two Voices. The Penguin Book Of First World War Poetry page 102

The Lark Above The Trenches. Scars Upon My Heart page 42

Munition Wages by Madeline Ida Bedford. Scars Upon My Heart page 7

The Penguin Book Of First World War Poetry page 13

Rycroft, Charles. Anxiety and Neurosis. Penguin Books. 1968.