Ancient Greece – Dream Beliefs

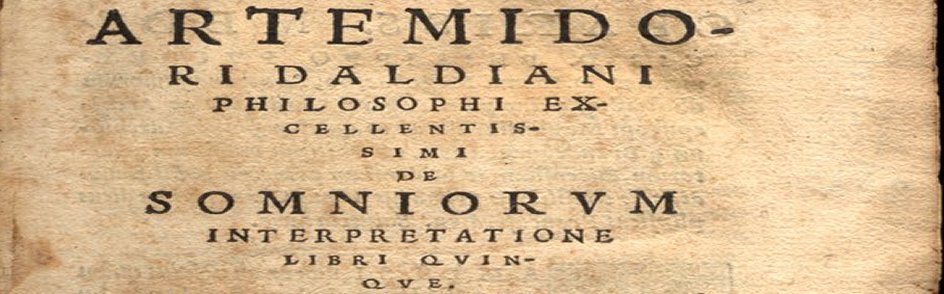

Antiphon, a Greek living in the fourth century BC., wrote the first known descriptive book of dreams. It was designed to be used for practical, and professional interpretations. He maintained that dreams are not created by supernatural powers but natural conditions. In the second century AD. a similar book was written by Artemidorus, a Greek physician who lived in Rome. He claimed to have gathered his information from ancient sources, possible from the Egyptian dream and the dream book dating from the second millennium BC. He may have used works from the Assurbanipal library, later destroyed, which held one of the most complete collections of dream literature. Artemidorus classified dreams into dreams, visions, oracles, fantasies and apparitions. He stated two classes of dreams; the somnium, which forecast events, and the insomnium, which are concerned with present matters. For the somnium dreams Artemidorus gave a dream dictionary. He said Abyss meant an impending danger, a dream of warning. Candle: to see one being lighted forecasts a birth; to exhibit a lighted candle augers contentment and prosperity; a dimly burning candle shows sickness, sadness and delay. This latter is taken from folklore of the times, and because dreams tend to use commonly used verbal images, was probably true. He maintained that a persons name – that is their identity, and the family, national and social background from which they arose – has bearing on what their dream means.

Plato 429 – 347 BC. said that even good men dream of uncontrolled and violent actions, including sexual aggression. These actions are not committed by good men while awake, but criminals act them out without guilt. Democritus said that dreams are not products of ethereal soul, but of visual impressions which influence our imagination. Aristotle 383 – 322 stated that dreams can predict future events. Earlier Hippocrates, the ‘father of medicine’ discovered that dreams can reveal the onset of organic illness. Such dreams, he said, can be seen as being illogically representing external reality.

Hippocrates was born on the island of Kos. On the island was the famous temple dedicated to Aesculapius the god of medicine. There were about 300 such temples in Greece alone, dedicated to healing through the use of dreams. Hippocrates was an Aesculapian, and learned his form of dream interpretation from them. In such temples the patient would have to ritually cleanse themselves by washing, and abstain from sex, alcohol and even food. They would then be led into what was sometimes a subterranean room in which were harmless snakes – these were the symbol of the god, and are the probable connecting link with the present day use of snakes to represent the healing professions. Prior to sleep the participants were led in evening payers to the god, and thus creating an atmosphere in which dreams of healing were induced. In the morning the patients were asked their dream, and it was expected they would dream an answer to their illness or problem. There are many attestations to the efficacy of this technique from patients.

“But how did a small, dirty, crowded city, surrounded by enemies and swathed in olive oil, manage to change the world? Was Athenian genius simply the convergence of “a happy set of circumstances,” as the historian Peter Watson has put it, or did the Athenians make their luck? This question has stumped historians and archaeologists for centuries, but the answer may lie in what we already know about life in Athens back in the day.

The ancient Athenians enjoyed a deeply intimate relationship with their city. Civic life was not optional, and the Athenians had a word for those who refused to participate in public affairs: idiotes. There was no such thing as an aloof, apathetic Athenian. “The man who took no interest in the affairs of state was not a man who minded his own business,” wrote the ancient historian Thucydides, “but a man who had no business being in Athens at all.” When it came to public projects, the Athenians spent lavishly. (And, if they could help it, with other people’s money—they paid for the construction of the Parthenon, among other things, with funds from the Delian League, an alliance of several Greek city-states formed to fend off the Persians.)

All of ancient Athens displayed a combination of the linear and the bent, the orderly and the chaotic. The Parthenon, perhaps the most famous structure of the ancient world, looks like the epitome of linear thinking, rational thought frozen in stone, but this is an illusion: The building has not a single straight line. Each column bends slightly this way or that. Within the city walls, you’d find both a clear-cut legal code and a frenzied marketplace, ruler-straight statues and streets that follow no discernible order.

In retrospect, many aspects of Athenian life—including the layout and character of the city itself—were conducive to creative thinking. The ancient Greeks did everything outdoors. A house was less a home than a dormitory, a place where most people spent fewer than 30 waking minutes each day. The rest of the time was spent in the marketplace, or working out at the gymnasium or the wrestling grounds, or perhaps strolling along the rolling hills that surround the city. Unlike today, the Greeks didn’t differentiate between physical and mental activity; Plato’s famous Academy, the progenitor of the modern university, was as much an athletic facility as an intellectual one. The Greeks viewed body and mind as two inseparable parts of a whole: A fit mind not attached to a fit body rendered both incomplete.

And in their efforts to nourish their minds, the Athenians built the world’s first global city. Master shipbuilders and sailors, they journeyed to Egypt, Mesopotamia, and beyond, bringing back the alphabet from the Phoenicians, medicine and sculpture from the Egyptians, mathematics from the Babylonians, literature from the Sumerians. The Athenians felt no shame in their intellectual pilfering. Of course, they took those borrowed ideas and put their own stamp on them—or, as Plato put it (with more than a touch of hubris): “What the Greeks borrow from foreigners, they perfect.”

Athens also welcomed foreigners themselves. They lived in profoundly insecure times, but rather than walling themselves off from the outside world like the Spartans, the Athenians allowed outsiders to roam the city freely even during wartime, often to the city’s benefit. (Some of the best-known sophists, for example, were foreign-born.)

It was part of what made Athens Athens—openness to foreign goods, new ideas, and, perhaps most importantly, odd people and strange ideas.

The city had more than its fair share of prominent homegrown eccentrics. Hippodamus, the father of urban planning, was known for his long hair, expensive jewelry, and cheap clothing, which he never changed, winter or summer. Athenians mocked Hippodamus for his eccentricities, yet they still assigned him the vital job of building their port city, Piraeus. The writer Diogenes, who regularly ridiculed the famous and powerful, lived in a wine barrel; the philosopher Cratylus, determined never to contradict himself, communicated only through simple gestures.

While they didn’t know that their time in the sun would be so brief, the Athenians did know, as their famed historian Herodotus once noted, that “human happiness never remains long in the same place.” Neither, it seems, does genius. ”

See: Aristides and the First Dream Diary

Comments

a friend and i had a similar dream about both being in a car accident, we do a lot of traveling so this alarms me in a way. i would like to know what this means

Cynthia – Some such dreams are about ones anxiety. But it could be a warning. But the future is not set in concrete and can be changed by what you do now. You can visualise a different end to the dream and even pray for protection.

See http://dreamhawk.com/dream-encyclopedia/peer-dream-group/#carryforward

But here is an Example:

I awakened one morning with a sense of foreboding and the word `ETIWANDA’ ringing through my mind. Realizing that I had probably failed to remember all of the dream, I simply prayed about it.

“Although it was early November, I was prompted to get out my Christmas card list and addresses. One of the first addresses I saw was the street-name Etiwanda. I called the friend who lived there and learned she was about to take a mountainous trip to Big Bear, Calif. I warned her to be especially careful and to pray for protection. When she returned from the trip, this is what she told me: `As I was coming around a sharp mountain curve, I heard brakes screeching. Because of your warning dream, I immediately drove completely off the highway onto the grass on the cliffside of the road. The next moment a sports car, out of control, came careening around the curve in my lane.'”

Tony

awesome

Jazmine – Thanks. Maybe read http://dreamhawk.com/dream-encyclopedia/babylonian-dream-beliefs/ – http://dreamhawk.com/dream-encyclopedia/15445/ and http://dreamhawk.com/dream-encyclopedia/mesopotamian-dream-beliefs/

Tony