Our Past or Present

I went to a great machine, a huge machine, ancient and massive. It is like the sort of fantasy machinery one sometimes sees in some films depicting the inside of a massive clock tower, with great wheels and spindles turning. As I watched this I gradually saw how it had developed over a long period of time. And this was portrayed by my going down underneath the top layer of columns and wheels, down to what was underneath them, what was motivating them.

As I went down in this way I realised I was looking at older and older levels of this enormous machine. Then my attention was caught by something dark, deep in the levels of this tower. It was a contrivance of torture. It was a machine to tear human beings apart. As I looked at this I realised I was looking at some of the deeps of my own being. I realised that my present self had developed out of the historical experience of my people, and not very far under the surface, not very far in the past, my forebears went through a period in which human torture was common and part of everyday life. It was demonstrated over and over. People would be flayed alive, hung drawn and quartered, torn apart on a rack – and this all to force subservience.

This was the past I have developed from. This is a part of the deep workings of my own being. It is this that we are still trying to grow away from. On the machine I saw human beings could be lashed onto it. They could be strung onto it and pierced, pulled apart. As this emerges into my awareness I realise that most of what I have been taught is that our present-day self, our reasoning mind, past to us from the Greeks, through the Romans, with influence from the Moorish culture, and this gives us our rational self of today. But what I see in these dimensions of the deep mind, are things that are never mentioned. I see that as well as this bright transcendent ability to reason, we also inherited and carry with us the memory of times of torture, of hatred and violence, of fiendish human life.

We know deep down that you could be hung for taking a piece of bread because you are hungry and starving – starved because of the dominance of those who have too much money, too much to eat. I was born in a country town, Amersham, where not so very long ago seven people were burned at the stake for daring to read the bible for themselves. Their names were, William Tylsworth (Joan Clarke his married daughter was compelled to light the faggots to burn her father), James Morden, Robert Rave, John Scrivenor, Thomas Holmes, Joan Norman and Thomas Barnard. All four were excommunicated and subsequently burned up on Rectory Hill overlooking Amersham.

I have, in my psychological past, that history. For many people, life in the past meant being subservient to the ruling class. But for some, God-fearing, God loving, may have meant recognising the threat, and remaining submissive. But for some it meant a sense of personal stature and quality despite one’s social status or class. For many, the martyrs represented the strength of human dignity, the power to stand up against oppression. It was the strength enabling people to challenge and change the world. it was a strength that could create a new path, strength to continue even when faced by death. They maintained their direction even though their bones formed part of the pathway that we now tread.

Some of us needed to do that. But even without facing death, forming a new path, blazing a trail, is not easy. This is because nearly everybody else, the establishment, are going in a different direction. Perhaps most of one’s friends or even family are going in a different direction. Something I am realising is that while our society is bringing awareness to things like sexism, and ageism, something that it hasn’t even started mentioning is elitism.

We know from recent events that the elite, the people with qualifications who form a part of the establishment, who may have given years of their life to gain their skill, in establishing their position and expertise, do not necessarily have a personal quality entitling them to their role. Their years of study do not make them infallible or even wise or kind human beings, like some doctors. We have seen that some of them are murderers. Some of them are a sexually perverted. Some of them use their position and authority to abuse men and women or children. They have sex with their clients or manipulate them towards financial gain. This is not to say that all these professionals are bad, but what it does point out is to say that because these people have qualifications, it does not mean they deserve our respect.

But the opposite is true also. Many of the unqualified are not idiots or “amateurs”. But very often they are treated as if they are of no account whatsoever. They are often dismissed. I had a personal experience of this while being interviewed over the telephone by a representative of the BBC. I was being asked to take part in a programme about dreams, something I was well qualified to do. The interview went very well and the person was on the point of asking me to participate in the programme, and they then asked me what qualifications I had. I said that my training was not one of scholarship. I had learned my skills through organising and running self-help groups for laymen and women. Without another word the person banged the phone down and ended the interview.

“Unqualified” people form an enormous reservoir of skill and experience. They often have years of work experience, a persistent inquiry, and are of great and wide study. Despite this they usually go completely unrecognized. Sometimes it is only in history they are given a place of honour because their work is still remembered and has become a part of the jigsaw upon which present knowledge is based. There certainly needs to be some recognition that elitism demeans or absolutely overlooks a huge amount of national resources.

Really take a look at the world you live in.

The beautiful….

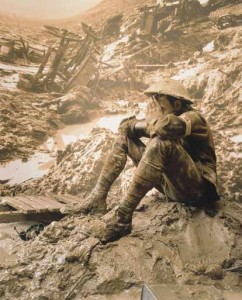

And the ugly…