Lord of the Flies by William Golding

To what extent is the novel concerned with social and historical contradictions in the period after the Second World War?

There is a clear indication in Lord of the Flies that the story deals with war and the effects of war. Even before characters other than Ralph and Piggy have been introduced, Piggy says to Ralph, “Didn’t you hear what the pilot said? About the atom bomb? They’re all dead. “2 This idea of mass death is later modified when Ralph sights a ship’s smoke at sea.3 The war is defined as still continuing by the narrator, and as being near at hand. He says, “… but there were other lights in the sky, that moved fast, winked or went out, though not even a faint popping came down from the battle fought at ten miles height. ” 4

|

Considering this setting to the story I do not feel there is a convincing argument for the novel being a comment on post war events or society in particular. What I will argue for however is that the novel is a many faceted comment on individual human and social conflicts as revealed during the years preceding Golding’s work on the book. These years include the World War II and the post war years. In particular I will explore what I consider to be the main theme of the novel, which is the relationship between various factors of individual and social life, as they are brought into play by powerful external events. In the novel the external events are war, the air-crash, and uncertainty in regard to the future. The factors of ‘individual and social life’ are those to do with cultural attitudes, propensities toward domination, leadership and organising of a social group. But even these issues are not clear-cut. Not only are various and changing responses to being marooned shown in the book, but also there are many different responses to and by individuals and the collective group. Some of these differences and shifts are shown in Ralph’s relationship with Piggy. Early in their relationship Piggy says to Ralph, “We got to find the others. We got to do something. “5 Piggy is obviously worried and wants action to feel assured. Ralph’s response is to ignore him. |

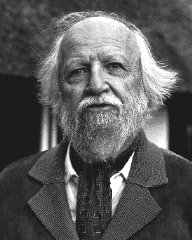

William Golding |

“Ralph said nothing. Here was a coral island. Protected from the sun, ignoring Piggy’s ill-omened talk, he dreamed pleasantly.”6

In this situation Piggy is actively pushing for an organising activity, but Ralph is lethargic and unconcerned. He treats Piggy with some coldness and disdain. At the end of the book however this disdain has completely disappeared, and Ralph is risking his life for the sake of his own conviction concerning social order. This is made clear where Golding writes, “And in the middle of them, with filthy body, matted hair, and unwiped nose, Ralph wept for the end of innocence, the darkness of man’s heart, and the fall through the air of the true, wise friend called Piggy.”7

The friendship between Ralph and Jack – “Jack and Ralph smiled at each other with shy liking”8 – was a friendship which become mortal enmity, and is another example of such shifts. Yet another interesting shift is that the group of choir boys who appear on the scene so disciplined and connected with religion, turn into the group who are highly barbarous.

Listening to some people’s comments on the novel, I have frequently heard the feelings expressed that the book is about violence and barbarism. Certainly it has that feature strongly evident, but in looking not simply at one part of the novel, the violence tends to highlight its opposite – Ralph and Piggy’s attempts to maintain a different social order for instance.

Conversely, Ralph and Piggy’s attempts to maintain this non-violent social order – despite their own frightening traits of violence9 – highlight Jack’s rule using physical force and brutality. So it is not enough to say the story is about barbarism. It would be more correct, but not entirely, to say it is about forms of social order conflicting with each other. The exceptions to this way of considering the novel exist in the figure of Simon and the ‘young ‘uns’. Simon in particular is an interesting character in the story. He is introduced as the boy who fainted,”… the choir boy who had fainted sat up against a palm trunk, smiled pallidly at Ralph and said that his name was Simon.”10 He becomes the companion of both Ralph and Jack, but has a discrete life of his own. That he is killed, and both Jack and Ralph are involved in some degree with his death, suggests unease with individuals who have their identity outside of the group. Piggy’s comment about Simon is, “He’s cracked.”11

Because of space I am purposely leaving out such possibly symbolic aspects of the story as the shape of the island being like a ship; the title of the novel,12 that there are only boys on the island, the various ‘monster’ images, etc. But I do think it is worth bringing in the fact that the island setting, with plentiful food and water easily obtained, and more than enough physical space, does add a particular factor to what happens. Common concepts of the causes of war are of them having economic or territorial roots. The island, however, is a wonderfully easy environment. The boys had no need to fight over food or lack of space. Nevertheless conflict and death ensue. Golding gives us clues to why this conflict emergence throughout the story. When Jack and Ralph first meet there is a direct contest for leadership. When Ralph was elected leader due to a larger vote,”.. the freckles on Jack’s face disappeared under a blush of mortification. ” Ralph senses the problem and quickly says, “The choir belongs to you of course. They could be the army. The suffusion drained away from Jack’s face.”13

Nevertheless the outsider, Simon, is still put to death. Ralph’s urge for peace also puts himself, Piggy and the younger children at risk, because he does not step in and make a stand against Jack before Jack gains power. This is very like the British people and politicians prior to the Second World War.

If there are direct contradictions depicted in the novel, this attempt to create peace amidst war-like actions is perhaps the most evident, and has certainly been, and still is, one of the greatest problems faced in this century.16 In the novel, Golding has Ralph and Piggy walk right up to the ‘Tribe’s’ stronghold. In finding courage to do this, to find a peaceful solution, Piggy says:

“I’m going to him (Jack) with this conch in my hands. I’m goin’ to say, you’re stronger than I am and you haven’t got asthma. You can see, I’m goin’ to say, and with both eyes. But I don’t ask for my glasses back, not as a favour. I don’t ask you to be a sport, I’ll say, not because you’re strong, but because what’s right’s right. Give me my glasses, I’m going to say – you got to!”17

Piggy, as a figure of moral conscience, is presented as a weak person, using Ralph to be his means of actively influencing the world. He takes the conch, as a symbol of each person’s right to be heard, and respected, and he pits it against a force in human nature that is without conscience or willingness to be moved by rational urgings to do what is ‘right’. He is killed for his efforts.

I see this as a possible comment on the ridiculously difficult, and yet called for action, of a peace-keeping force such as United Nations, to enter a battle arena where both sides are driven in compulsive urgency to wipe out all opposition. If the peace-keeping force hold out the conch shell, will it be any more effective than was Piggy’s effort? As Douglas Heard said on Radio Four recently, “What is one to do, bomb them into submission?”

The solution to this in Golding’s novel is the arrival of a British naval cruiser, and a “naval officer” standing on the beach. This ‘higher power immediately robs Ralph, Jack, and his ‘Tribe’, of their authority, and eliminates their rivalry. Yet it is a vessel of war that brings this peace, an ambassador of war its representative. Here I think is one of the most devastating contradictions faced in this century. In an attempt to keep peace, many or the world’s nations developed and held the most destructive weapons ever known.

So in summarising, I see the implications of the novel as suggesting that when an ‘adult’ – a powerful and organised body of people – is not overshadowing the behaviour of social groups, these polarise into conflicting bodies. A recent example of this is the withdrawal of Russian power from what were colonies, or occupied countries. Schisms formed and bloody war followed. Such groups often develop a sort of organic integrity such as our body does. Individuals or groups exterior to this integrity are sensed as threats – just as our body senses many bacteria as threats and kills them – millions each day. It also appears innate in human beings to elect leaders, and polarise around such leaders, often in opposing groups. Of course, there are many other ways of existing in society, and Golding gives us Simon as one such example. But because of the factor of integrity within groups, such outsiders are often felt as threats by both sides. Hitler’s ‘tribe’ not only killed the Jews, but also any individualists who had their own opinions about his party.

Golding does not appear to work out this difficulty in any other way than restating it in a readable form. His resolution is the re-introduction of the ‘adult’ in war garb.

1 Lord of The Flies – by William Golding. Published by Faber and Faber in 1954. Version used is the paperback edition published in 1958. ISBN: 0-571-08483-4. 2 Page 14.

3 Page 71

4 Page 104

5 Page 15

6 Page 15

7 Page 223

8 Page 25

9 Piggy and Ralph are disturbed by and afraid of their guilt after the death of Simon. Page 172

10 Page 23

11 Page 146

12 The Lord of the Flies is also the name of an Assyrian demon, the Pazuzu. According to the Assyrian mythology, this demon tries to destroy the space of the universe. Golding possibly used this name allegorically (the human nature is the “Lord of the Flies”, the Pazuzu, the creature which is trying to destroy space/the world). Quoted with thanks to Velissarios Valsamas from an Internet page on Golding.

13 Page 24/25

14 Page 130

15 Page 130

16 Northern Ireland, Korea, Viet Nam, African States, Bosnia, Yugoslavia.

17 Page 189

|

|