William Blake – Psychologist

Blake may shock us sometimes with what he says, but at all times his sight is from what he can clearly see in human nature.

One of the interesting statements made by modern psychology, is that the past actually is a living principle in each individual. In fact, it is stated in some textbooks that the great men and women of the past live on within us. Dr. G. R. Heyer, in his book ‘Organism of the Mind’ says “We all have a psychological ancestry as well as a physical one. In us Germans, Goethe still lives on, not alone superficially, in our conscious memory, but in our more hidden thoughts, our imagery, our behaviour, and our feelings, as a mental ‘gene’. The same is true of all the great, of all the immortals, as far back as Jesus Christ and further.”

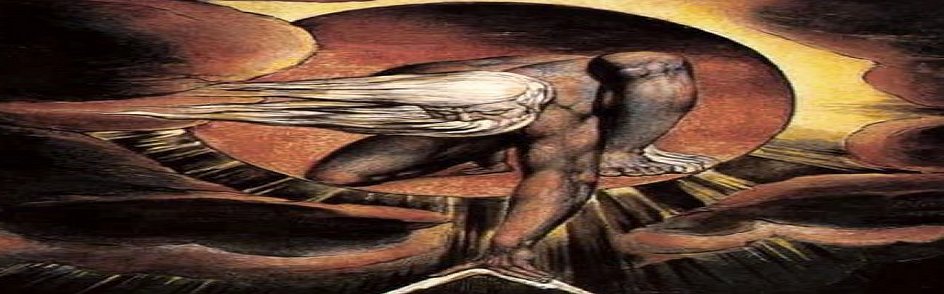

If this is true, then it must be of value to study the lives of such men to see what there is of them in us. William Blake, poet, artist, philosopher, mystic, and as I hope to show – psychologist – being so near to us in ways of birth, historical distance and background, must be of particular importance. It is hoped that this is enough excuse for us to indulge ourselves a little in this man’s inner life. The enjoyment that one can thereby obtain from a study of Blake’s thought, is heightened also by his subtlety and very great humanity.

Probably some of his most obvious psychological expressions are made in ‘The Marriage of Heaven and Hell’. We read for instance the statements, “Those who restrain desire, do so because theirs is weak enough to be restrained.” and “Sooner murder an infant in its cradle than nurse unacted desires.” When we realise that such verses were published in 1790, long before the advent of modern psychiatry, we cannot help but respect this man’s insight into human nature. The very title of this work, ‘The Marriage of Heaven and Hell’, is also an expression of Blake’s philosophy. He maintained that there was no lower nature in man in the sense of being inferior or evil. For him, Heaven was a Poetic or creative genius in man, or what today would be called the superconscious. Hell was man’s body and all the energies of movement, emotions and delight that it generated. He mocked the conventional outlook of the churches of his day over this, for Hell to him was a necessary and delightful aspect of man’s nature when rightly seen. He writes “I was walking among the fires of Hell, delighted with the enjoyments of genius, which to Angels look like torment and insanity.” He felt that one must find some sort of harmonious relationship with what is called the highest and lowest in man. A’-though he would not admit that there was any true differentiation between them, rather that they were merely different aspects of the same creative process. “Man has no body distinct from his Soul; for that called Body is a portion of Soul, discerned by the five Senses, the chief inlets of Soul in this age.” In fact he says that without contraries or opposites there is no progression.

Blake felt that within man was the source of all wisdom, power and love. He expressed time and time again how men should at all times attempt to release the tremendous inner potentials that are his birthright Because of his yearnings to achieve this in himself and in society, he became the enemy of the established church. This does not mean that he saw anti-Christian – a man who wrote Jerusalem could not be that. He saw in the dogmas of the church the chains that prevented men from expressing the real and natural life within them. He attempted to explain to the society of his day that “Energy is the only life, and is from the Body; and Reason is the bound, or outward circumference of Energy.” As we have found, dogma, or too much reason, literally does ‘bound’ this inner life and prevent its expression. Rather bitterly, through such feelings, he says that “Prisons are built with stones of law; brothels with bricks of Religion.” Certainly the foolish repression of natural energies may in many lives lead eventually to an unhealthy or destructive expression of these same forces.

Jung writes in his works that one should allow fantasies to arise in the mind, and that if we would seek to understand life we must enter into it. Blake has again apprehended such findings. He believed that “If the fool would persist In his folly he would become wise.” and “You never know what is enough unless you know what is more than enough.” Being also something of a scientist or experimenter with life itself, he felt that provided one was indeed seeking the truth, “The Road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom.” One should not judge this statement too quickly. Blake was not a licentious man, nor had he been. But he did allow his nature wider bounds of expression than most men of his day. His excess was one of the soul, which he refused to shackle with the limiting conventions of his time. His attitude was to experiment with life, accept nothing until you know, “Drive your cart and your plough over the bones of the dead.” The past is dead, follow the path of the present. The past is in us and expresses through us, but such forces are generative bringing about ever new forms, not the – dead laws of the Pharisees. “I must create a System, – or be enslaved by another Man’s; I will not Reason or Compare, my business is to Create” he writes.

One might even imagine Blake saying “Can man ever be perfect? Is the idea of perfection itself not relative to our desires-, our viewpoint and our function?” But he says the same thing in his usual synthesised manner when he states “Mutual Forgiveness of each vice, such are the gates of Paradise.” Later, in a Meditation on Jesus he writes, “Now hear how He (Jesus) has given his sanction to the law of the ten commandments. Did He not mock at the Sabbath, and so mock the Sabbath’s God; murder those who were murdered because of Him; turn away the law from the woman taken in adultery; steal the labour of others to support Him; bear false witness when He omitted making a defence before Pilate; covet when He prayed for His disciples, and when He bade them shake off the dust of their feet against such as refused to lodge them? I tell you, no virtue ”

Again upon this point, Blake can be greatly misunderstood. In these sentences he seems to be attempting to show that set moral codes are only a working guide. When he says Jesus acted ‘upon impulse we have Blake’s ideal of the Poetic Genius expressing again. To react to circumstances and environment according to the prompting of our higher consciousness, and not from reasoning upon the Law.

In Jesus and the Pharisees we can see a psychological drama taking place if we interpret it according to Blake’s key. In Jesus we have the higher consciousness at work, reacting and expressing according to its universal scope. The Pharisees are the reasoning mind, always questioning, but lacking contact and power over the creative life giving forces in the universe. Reason also cannot surpass itself as does intuition, for it depends upon already revealed law and cannot enter the unknown.

Reason, because of its limitations cannot understand what Jesus symbolises; and because this higher consciousness urges us at times to do what may seem to be against our reason, the reason in us may even sacrifice this divine aspect of ourselves.

One can see in this use of symbolism another aspect of Blake’s understanding of man’s inner nature. In modern psychology it is explained that people, objects and places are used in dreams as symbols of inner conditions or realisations. Blake used this principle a great deal in his poetic expression. This is especially noticeable in his ‘Jerusalem’. For him the towns and hamlets he knew were symbolical of various shades of feeling and life.

Symbolical also was the sexual act and the intercourse between men and women. Unlike his contemporaries, he could not see that the human nature was a snare keeping men from the divine. He felt that “Whatsoever lives is holy”, and as passion lived in him and nature, it must have its place in things. It is the steam that drives the engine of creation when rightly used, and Blake would not indulge himself in the practices of the ascetics. Passion became for him the fiery sap rising in the tree, which when united with the ‘breath of life’, the radiant energies of the Sun, becomes something vitally alive, responsive and creative.

What then shall we think of this man? Shall we think of him as a genius? Was he one in whom intellect was so acute as to enable him to foreshadow the outcome of our present psychiatric knowledge? Or should we think of him as he may have thought of himself-as one who had contacted the Poetic Genius in himself, and like all those before or since who, having found the fountain of living water, was able to con-found the reason of their times. In his own words “What is now proved was once imagined.” Blake then was surely the embodied imagination of England’s Eighteenth Century, expressing in print, in art and in life. If we can find something of this man alive in ourselves, then it is a happy moment for us. If besides finding it we can allow it to flourish and bloom, then we may say as he did:

Bring me my Bow of burning gold -Bring me my arrows of desire; Bring me my spear; O clouds, unfold! Bring me my Chariot of Fire!

I will not cease from mental fight, Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand, Till we have built Jerusalem, In England’s green and pleasant land.