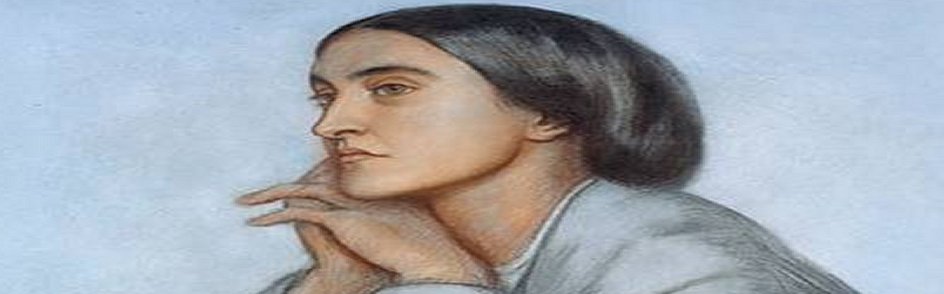

Women Poets – Rosetti and Browning

The poems of Rossetti and Barrett Browning present a complex image and description of women and the times the poets lived in. One of the impressions their poems give collectively is that of looking back and maintaining the romanticism and standards of the past. Another is of looking ahead and glimpsing the modern movement toward emancipation and individuation, toward more options in relationship and work.

In Rossetti’s Goblin Market she starts with the words:

Morning and evening

Maids hear the goblins cry:

Come buy our orchard fruits

The narrator here starts as if telling a story, one in which there is no personal involvement. There is a powerful statement however that maids hear goblin voices that call for their custom. The word maid refers to an unmarried woman, and goblin to a mythical and mischievous and ugly non-human male being. Something is being offered to presumed virgins that they must pay for. Soon afterwards in the poem appear the lines:

Laura bowed her head to hear,

Lizzie veiled her blushes:

Here two opposing characters are introduced by the narrator, and a direct description of two different responses to the same situation portrayed – the goblin call. Laura is trying to hear. She is attracted and does not veil it. Lizzie is likewise responding, and her blushes suggest some personal feeling which either embarrasses her or excites her, maybe both. Is she in fact feeling excitement but also experiencing some sort of social embarrassment? Further along, after Laura has gorged on the fruit which Lizzie has assured her is forbidden; after she has “sucked and sucked and sucked” on it, and returns to the river with Lizzie, she no longer hears the goblin voices – but Lizzie does. The meaning is surely that the voices are purely subjective. Like a fantasy love, once it is tasted the glamour, the seductiveness, the allure and charisma may disappear. If so, where does the seductive voice emerge from? At least, where does the illusion emerge from?

Laura and Lizzie appear to be meeting the fantasies unmarried and sexually unsatisfied young women now admit they experience. Laura “sucked and sucked”, Lizzie was aware of or afraid of the outcome. These two women are certainly not described as innocents. Laura has already tasted the fruits. Even if fruit only symbolises temptation, to know temptation that deeply suggests a loss of innocence even if virginity is maintained – “She sucked until her lips were sore.” That they also lie together “Cheek to cheek and breast to breast” also points out they are not innocents in comforting each other. Other lines have a directly sexual symbolism, such as Laura walking home:

Trudged home, her pitcher dripping all the way;

So crept to bed and lay

Silent till Lizzie slept;

Then sat up in a passionate yearning,

And gnashed her teeth for baulked desire, and wept

As if her heart would break.

This is no description of an innocent woman who does not know the power of sexual longing. The pitcher can easily be recognised as the vagina, oozing in longing, just as the male penis does. Then, in case we are in doubt, the narrator tells us of passionate yearning and baulked desire.

In the mention of money as payment, and adding ‘Market’ to the title, the poem brings in the accompanying complexities of sex for women at that time, or perhaps in the life of Rossetti herself. The lack of efficient birth control, disease, and the economics of relationship were all a part of that complexity. However, when Lizzie has what might be a neurotic or subjective experience of sex; when she “Knew not was it night or day”, she gains a power of either self satisfaction – auoteroticism – or something that enables her to stand in a male role with Laura. Then Laura, in what is a fairly straight description of a lesbian relationship, “… kissed and kissed her with a hungry mouth.”

The poem ends by placing the heroines in the role of caring mothers. Switching to the voice of Laura, the narrator gives us the motto that her sister stood in “deadly peril to do her good.” So the difficulties of a woman facing sexual drive, of restraining it from licentious behaviour and even passing through the fiery pleasure of a lesbian relationship with her sister, are described. The story is an allegory exploring what a woman in that period might face in awakening sexually. It looks at possible ways of dealing with such an awakening.

Barrett Browning, in Lord Walter’s Wife, takes a very different stand to the question of fidelity and sexual desire. After a direct stand for infidelity, Lord Walter’s wife says to the anxious male who is avoiding her advances and calling her hateful:

“Her eyes blazed upon him – ‘And you! You bring us your vices so near

That we smell them! You think in our presence a thought t’would defame

us to hear!

This very powerful passage completely reverses the argument, which was usually that any woman who did not remain ‘virtuous’ was a harlot, a ‘fallen woman’. The lines imply that a man considers it virtuous to feel desire for a woman so strongly she can ‘smell’ it when he is near her, as long as he doesn’t give in to it. Even if he does occasionally have sex with a woman other than his wife, it is only a small misdemeanour. But if a woman simply expresses her desire for such a relationship, she is “ugly and hateful.” Meanwhile the man can think such things that if a woman were known to have taken part in hearing them, she would be labelled as complying with them.

Another aspect of trying to integrate the best of womanhood past, with what was felt to be the emergence of womanhood future, was the question of single motherhood and an illegitimate child. Barrett Browning addresses this in her long poem Aurora Leigh. In the poem this is considered alongside the quest for personal expression and success outside of a male/female relationship. The character Marian features as the woman who is abused and gives birth to an illegitimate child. About the single mother and her child Aurora argues that:

“She is no mother but a kidnapper,

And he’s a dismal orphan, not a son”

Marian answers in reply:

“… the child takes his chance;

Not much worse off in being fatherless

Than I was, fathered.”

The narrator, by having the two voices, Aurora and Marian, can explore more easily the pros and cons of illegitimacy. Obviously there is tension and conflict between these two views, and the attempt to meet this conflict about the old order and the emerging new is certainly something one can identify in the poems.

Another facet of the emergence was whether a woman should take the male role. Barrett Browning’s poem To George Sand seems to stand for the woman acclaiming her womanhood rather than trying to be a male.

“True genius, but true woman! dost deny

The woman’s nature with a manly scorn,

And break away the gauds and armlets worn

By weaker women in captivity?”

Putting the ‘but’ in the middle of the first statement brings extra attention to the words ‘true woman’. It is like saying, “You may be a genius dressed as a man, BUT you are actually a woman. Do you deny that?” There might be some question as to whether the words are suggesting the woman should use ‘manly scorn’ as a weapon. The following words, “Ah, vain denial” clarify this however. This is a difficult passage however, as if the placing of the exclamation mark is a full stop as it usually is, then the meaning is as suggested. If it is not a full stop, then Barrett Browning is encouraging women to take the role of male.

Later the poem says:

“… and while before

The world thou burnest in a poet-fire,

We see thy woman heart beat evermore

Through the large flame”

Just prior to these lines, the words “Disproving thy man’s name” appear. Is this a note of disapproval as well as a statement that acting like a man doesn’t make a woman a man? If not, what essentially is the woman in these poems? Who is she?

Considering that Barrett Browning in her poem To George Sand, describes Sand as “Thou large brained woman and large hearted man” there is some dichotomy about what is woman and what is man. So the argument for woman begins to partly seem like an argument for a psychic sexual mobility – a mobility of the psyche. One can have a male or female body, and yet psychologically one can have attributes that are often considered those of the opposite sex. A man may want to hold his baby to his breast even if he does not have the physical equipment to feed it. The woman may have the ability to defend and struggle in the world, even if her body continues to menstruate to be ready for childbearing. The Greeks embodied this idea in the statuary of the hermaphrodite. Is that what Barrett Browning is hinting at in the line, “Till God unsex thee on the heavenly shore”?

The difficulties women felt at the time, as suggested, were many sided. No wonder there were so many women who retired to their bed. With so much social and personal conflict, so much at stake, retreat may at times have been wise.

In summary the poems of Barrett Browning and Rossetti frequently present the woman as an individual, and social unit, and a force in society. She is someone who is reaching toward massive change, but is still carrying the social and personal attitudes, the burden of established laws and customs, the “gauds” acting as a burden or means of captivity. This woman is attempting sexual, marital and vocational reform. She is gradually achieving it, but with much struggle, frustration and self-searching. She is trying to define what it is to be a woman, a mother, a lover, a force in society. She is also a goad to men to attempt change themselves. Such changes however, are not without enormous doubts, and not without the need to define her emerging self. In large part, the poems can be seen often to be working at this task of definition – or at least the exploration of it.