Count Arthur Tarnowski

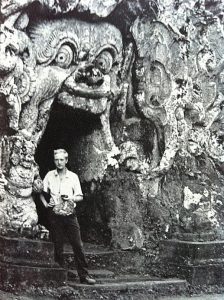

Today is the 8th anniversary of my father’s death. As I’ve experienced more systems change training I’ve been remembering and praying to my father on an almost daily basis. He understood systems change, geopolitics, history and the challenges we’re experiencing in our life. He was born into the Polish Aristocracy in 1929, was a member of the Polish Resistance and hid Jews in the ceiling above where Nazis we’re living. He was then starved in prison only to escape and be on the run travelling underground with a price on his head. He came to the UK with nothing as a war-torn refugee. He set out backpacking from 1953–1958 working as a guide in places of antiquity like Egypt, Greece, Turkey, Iran and Iraq. He was setting up a company to take students overland to India in the ’50s with a mission to prevent future violence through better understanding and empathy between East and West. He would live as most of the world did — often on the streets to build up his understanding of the human condition. He was writing the first guide books for how to travel on a shoestring budget. In 1958 he was writing the first backpacker guidebook for Bali and contracted polio. He spent 2 years in hospital and the rest of his life paralysed fro the waist down and in a wheelchair.

He then spent 4 years preparing for a historic expedition where he travelled around the world between 1964–1967 in his wheelchair on the Unbeaten Track Expedition. He filmed documentaries for the BBC, wrote for the Readers Digest, published the Unbeaten Track book and touched the lives of many thousands of people. He then devoted much of his life to the work of Baba Amte and the Anandwan community in India. He became the adopted son of Baba, one of India’s most notable social workers and whom Gandhi called the ‘Conqueror of fear’. He visited Baba almost every year from 1964 until he could no longer travel in 2010–44 times. He created a rehabilitation Center that trained many thousands of handicapped people in vocational employment skills. He undoubtedly lived life as a great ancestor.

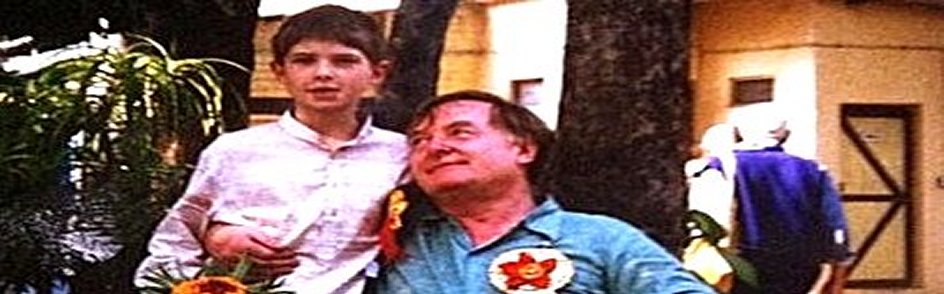

But who was my father to me? He was a profoundly inspiring friend and parent. I grew up travelling much of the world with him. Most years we’d travel to India at Christmas, Turkey at Easter and all sorts of places in the Summer — from the Silk Route through Pakistan into the Himalayas to the length and breadth of Iran. With him, as an intrepid guide, we’d live as locals do with a never-ending enquiry into the state of the world.

I feel privileged beyond any words for the parents I was born to. Everything was a lesson with my father. I learnt about the population explosion, regenerative farming, water irrigation, past Civilisations, Spartan values, health, education, food systems, all forms of mythology, religion and spirituality, initiation rituals, geopolitics, and so much more. He wanted my brother and I to have the broadest education possible. Dad made it clear to me that I would experience a complete societal collapse in my lifetime and that I could do something about it. In fact, I believed he trained me for my own Dharma. He often said ‘Society is one missed meal from anarchy’. He raised me with a sense that our Polish nobility was nothing to do with our castles, titles and wealth. It was about how you show up in a time of crisis. He’d remind that true nobility sits in the heart. The virtues he passed on from 28 generations of Tarnowski’s were rectitude, honour, self-command and above all courage. I’ve never met a greater living example of what it means to live life as a great ancestor to the future.

As I spend often 8 hours a day playing the Unified Planet Game speaking of systems change and envisioning a brighter future, I’m reminded of my father’s lessons on an almost daily basis. I feel so grateful to have an unshakable clarity for my own purpose and commitment to make conscious choices anchored to a vision of a thriving future for all life. There is no greater inheritance than this. I believe this is the practice of living one’s life as a great ancestor to future generations.

As I’ve spent more time in ritual and prayer to honour my ancestors, I’ve learnt a great deal about my own life and legacy. In my prayers, I often enter a council of my ancestors guiding my choices and actions. I don’t believe it is random that my seventh generation grandparents are Catherine The Great, Empress of Russia and John Jacob Astor. It is not random that every one of my ancestral lines made their mark on history. The more I listen the more I can hear the music of my family. When we recognise the music we can dance to its melody. I believe the answer to bridging the chasm between left and right politics and win-lose finite games is to go back in time in order to go forwards. I believe if more of us could connect to our ancestry and history we could connect with our future. The ancient and the future are kismetly entwined. This is something every indigenous tradition has known and practised intimately. As Ram Dass said ‘We’re all just walking each other home’.

Today, I am holding vigil space for my father. I invite his continued wisdom and guidance on how I show up in response to the needs of the world. I bow in gratitude to his never-ending lessons that provided me the richest of soil to grow deep roots into my soul purpose. I have lost in life my best friend, mentor and father. But through our love, I’ve gained so much more.

I close with a randomly chosen passage from Dad’s book, the Unbeaten Track:

“By the time we reached India in September 1964, we had clocked up 10,000 miles; by the end of that year, the mileometer showed 21,000. Although I always made a point of calling in at hospitals, normally in the larger cities, we spent most of our time in the country, well away from main towns and trunk roads. After a while, we felt that we had never known modern conveniences. We camped out wherever our fancy took us, a long way from camping site regulations and restrictions; we shared the simple life with the villagers we met, and felt honoured when they invited us in to share a meal, or to spend the night with mud walls and thatch around us.

But there was‘ no inverted snobbery about this. Since four Asians out of five live in villages, in conditions that would strike most Westerners as primitive beyond belief, it seemed to me that if my ‘random sampling’ of the disabled was to be fair and acceptable, we should spend roughly four times as much time off the beaten track as we spent in the cities. But as the weeks turned to months, I realised that the pattern was very different from what I had visualized, sitting in the cosy warmth of a London flat.

As I talked with cripples, day after day, from early morning until late at night, in their homes or in the streets, sharing their hopes and problems, I entered a new world, a world of hopelessness and misery that few Westerners have ever penetrated. This may sound conceited, but most visitors from abroad seldom stray far from a well-worn path, scurrying busily between their tourist hotel, some ancient monument and perhaps the clinical, germ-free atmosphere of the modern hospital ward.

The more immersed I became in this work, the more I found that my own values and outlook were beginning to change. Meeting an orphaned child lying on the pavement with both legs amputated, my own problems and worries appeared ridiculous in comparison. After all, what does a tax demand, or a better flat, or a vacation abroad really mean when confronted by someone who is literally starving, whose last meal several days previously consisted of undigested grains rinsed from cow droppings? What price a smart kitchen, or a new car, when you meet a crippled girl condemned to a life of begging because her parents can’t afford tuppence a day for her bus fare to school? Many argue that such comparisons are unrealistic and unfair. Up to a point, they may be right. But they have never lived, I suspect, in the East, and have never had the opportunity of finding out for themselves how the less fortunate live, how little is asked of life.”

Last photo taken in Bali in 1958 before contracting polio and being wheelchair bound.