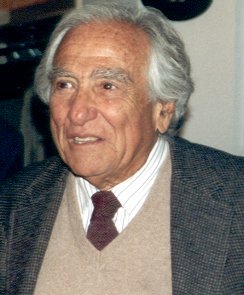

Janiger, Oscar

Was a Beverly Hills psychiatrist who “turned on” scores of artists, intellectuals and elite members of Hollywood’s entertainment community, including the late Cary Grant, to the psychedelic drug LSD in the 1950s and 1960s, died at 83.

Janiger died on Tuesday August 14, 2001 of kidney and heart failure at Little Company of Mary Hospital in suburban Torrance, spokeswoman Laurie Hanley said. He maintained a therapy practice until just a few weeks before the end of his life. He was survived by a sister and two sons.

From 1954 until 1962 — four years before LSD was declared illegal — Janiger was one of the first researchers to probe the drug’s potential for enhancing intellect and creativity. He incorporated the drug into his therapy and handed it out to an estimated 1,000 volunteers including such luminaries as novelists Anais Nin and Aldous Huxley, actors Cary Grant and Jack Nicholson, and conductor/composer Andre Previn.

Janiger often said he was particularly interested in artists’ ability to access a state of altered consciousness in uniform conditions using this creativity pill,” which he saw as a “marvellous instrument to learn more about the mind.”

Although his research predated that of Timothy Leary, it was never widely recognised because he never published his data.

Born in 1918 in New York, Janiger became interested in psychiatry at age 7 when, upon taking long walks in the country, he realised that his imagination could create a whole new cast of characters on the same long road each night. “From then on when I’d get into situations, I’d determine what aspect that was within me was being projected outward, and what was a reflection of the world that others can validate along with me. That, of course, has been the theme of my work in therapy and as a scientist,” he said during a 1990 interview.

250 WORKS OF ART

Janiger received his MA in cell physiology from Columbia University. For a time he worked as a New York City high school teacher but got reprimanded for pasting stars on the classroom ceiling. He ultimately quit after being reprimanded again for bringing mouldy bread, cheese and wine into the classroom to teach children about the advent of penicillin. He went on to the University of California Irvine School of Medicine, where he served on the faculty in their Psychiatric department for more than 20 years in addition to maintaining a private practice in Beverly Hills.

Unlike the LSD field tests conducted by the United States government, Janiger’s subjects were fully aware they were being given the drug and each paid $20 for a “hit” of “acid” which was made by a Swiss pharmaceutical firm. Janiger gave his patients the LSD in a room that adjoined a garden in his office rather than hospital or prison settings that had typically been used in previous government tests. He personally took LSD 13 times and said that it helped him see that “many, many things were possible.”

About 70 of his patients took part in a creativity experiment in which he asked them to paint or draw an American Indian Kachina Doll before taking the LSD and then again one hour after taking it. Some 250 works of art were created during those sessions.

Affectionately nicknamed “Oz,” as in “wizard,” by his friends, Janiger’s interests were wide ranging. After LSD was outlawed in 1966 he remained an advocate of the drug but turned his attention to other research.

Among his many accomplishments he established a relationship between hormonal cycling and pre-menstrual depression in women, discovered blood proteins specific to male homosexuality, and determined through studies of the Huichol Indians in Mexico that centuries of peyote use do not cause chromosomal damage.

The second largest study Jaqniger conducted involved an examination in artists of the contribution that LSD could play in the creative process. The artists reported that in their LSD experiences they had gained the ability to generate original insights, fresh perspectives and novel, creative ways to express themselves through their art. One artist reported that he “broke the tyranny of form.” To my surprise, I found that there was a substantial learning curve and that artists gradually become more adept working under the influence of LSD. The artists somehow found a way to draw inspiration from the LSD state for the creation of art and were able to increasingly control the physical expression of their subjective vision. The artists who were most able to represent in their art their subjective LSD experiences were those who had most developed their technical abilities, so that they had the rigor to bring back to consensual reality their artistic vision which one artist stated, “was more creative than a dream, more original than a madman.”

Janiger also describes a sub-study related to the psycho-physiology of pain blocking. This study was examining whether LSD could act like a dissociative anesthetic:

“For example, we took him to this man who was a professor of dentistry at UCLA, who extracted his tooth. He didn’t use any anesthesia. And the subject had no pain. The dentist said later that he was astonished because he had touched the man’s nerve with his instrument and he didn’t respond. He said it was the only time he’d ever seen that a person was able to tolerate that, when there was no anesthesia.”

How large of a dose did he get?

About a thousand micrograms.