Autobiography of a Premature Baby

I am now one of the silver haired males in our society. While I was still a dark haired young man I used to think I would end my days as someone extraordinary. The reason being that I was taking risks in unconventional ways, delving deeply into the unconscious, meeting things that most people try to avoid in themselves. However, I now appear to myself as a person on the street you wouldn’t give a second glance to. I do not have an important role. People do not look to me for something. I am not an accredited expert in any field – accredited by the establishment that is. But in gaining my silver haired status I made an incredible journey. It was not a journey to the lost islands of the Pacific, or a sojourn with a hidden Amazonian tribe. It was a journey into myself. It was an Odyssey through adventures that took courage. At times it scared the pants off me. On that journey I met the savage that dwells in us all. I had to search into dungeons to find my abandoned and terrified infant self. I struggled with the snake of sexual power, and fought and made friends with the dogs and creatures of my own instincts. Finding beings of light and love I knelt before them to gain their wholeness and wisdom, and climbed the mountain beyond their cave to see the view and from that view found healing.

It was certainly a journey that only a few others were willing to take with me. It was also a voyage to the source of the living rivers that flow into the world as you and me. In other words I managed to find my way Home, back to the Source, into the wonderful Garden. I walked in the High Pasture and gave myself to that shimmering ever-shifting eternal moment that is at the heart of all things.

That is why I want to tell you my story.

My birth took place about ten in the morning on May the tenth 1937. I was born in the upstairs room of a small house in Amersham High Street, nearly opposite what used to be the old fire station. My birth was two months premature, and in the thirties there was no nearby hospital intensive care unit for me to be nurtured in. My hearsay is that my mother had a prolonged and difficult labour due to the conception taking place at the end of a fallopian tube. At my birth the attending doctor pronounced me dead, threw my body to one side on the bed, and said, “Let’s look after the mother.”

His aside was to my grandmother who took no regard of his suggestion and quickly carried me off to dip me in hot and cold water to start me breathing. My life is a testament to her skill. She had mothered thirteen children herself, some of whom had died, and I have a sense of her bearing an old and deep wisdom passed on through generations of women. I can barely glimpse the motivations she might have felt, and it leaves me with the question as to why she gave me life.

What I missed out of the story was that the gap between my thrown aside body and my grandmothers resurrection was that I had a near death experience. That because my lifeline, my umbilical cord, was cut early and I was not breathing, so the delay led to my dying. I know many people cannot believe that a baby can remember such things. Well true they cannot remember as we do with words and images, but all life forms have enormous emotional responses and are known to experience a conditioned reflex. Whatever it was caused my baby self to remember, the experience left me with the desire to share the experience, to communicate to others about the wonder that we all are, about health of our body and amazing world death reveals to us. See The Baby Who Became Tony

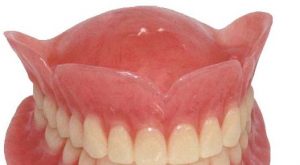

It took ages to realise that I was born a runt – a small or weak person – that could not function as normal healthy people can. I didn’t realise the extent of its influence until I journeyed to Australia and had to have a full medical examination to enter. The woman doctor, a very efficient and straight-out person, asked me did I know I was born prematurely? I said I did and asked her how she knew. She said, look at the roof of your mouth, it shows your body never completed its growth.

I am one of the unborn. I have maintained a level of awareness that is natural in the womb, but that most people leave behind before they are born. This enables me to do things in my mind that are not easy for other people. The so called religious seers are freaks, people like me who maintain unusual levels of awareness. They look at life through different perspectives. I look at life through the eyes of the afterlife, or the prebirth, but it fucks up my ‘normal’ life quite extensively.”

When I was born childbirth was surrounded by very different attitudes than exist today. The shadow of enormous mortality still fell over mothers and babies, and it influenced doctors. Antibiotics didn’t exist. Infant care was not developed to the degree it is now. The doctor was telling my mother and grandmother a straightforward and accepted truth of the times – ‘Why attempt to give life to this premature and tiny baby? It will be difficult to rear, more prone to illness, and it will be harder for it to cope with life. It isn’t breathing at the moment, so forget it and try again for a healthy baby. Leave it’.

I ask such a question because the doctor’s words were not flung out casually. Each of us is a witness to our times. We all exist within a huge web of influences and understandings, and if I try to grasp the view from which the doctor’s words arose, there is sense in what he implied. If we have children and say to one of them as he or she goes out the door, “Be careful”, we don’t need to mention all the things in today’s world that one needs to be careful of. If the child is old enough to manage the streets alone, they can already fill in most of the details about dangers they should avoid, such as drug pushers, muggers, child molesters, and other violent children.

The moment of our destiny

I am still uncertain if there is any truth in modern astrology, but I do know the moment and experience of our birth stamps us with indelible marks of destiny. It cuts us with injuries. It plants seeds of opportunity, and unfolds countless connections with the past out of which we can weave a future. Our birth does this in very apparent ways, not at all mysterious. But perhaps we overlook or ignore them. A lively extrovert Australian male doctor once told me part of his life story that explains this. Two of the big birth factors for him were that both his parents were Jewish, and both parents were the sole surviving members of their respective families after the Holocaust. This had coloured his life so much that he was led to the realisation he could be murdered for no other reason than being himself – in the case of his forebears this meant being Jewish. Out of our conversations he had come to realise for the first time, and with a shock, that this unconscious realisation of unreasonable death had been a push from within for him to work hard to become a doctor. His equally unconscious reasoning about this had been that if he managed to become a doctor, then he would be the last one to be thrown overboard when murder was on the loose – even murderers need doctors.

Apart from my premature birth, the shaping forces in my own life were the year, the mixed cultural background provided by my parents, and their different temperaments. But there are roots of influence underlying birth itself, and those roots draw sustenance from our conception. It is from the wonder of that moment that our life unfolds or blossoms to whatever colour and form it does. The moments of love that led to conception create a subtle matrix that shapes us. I have no formed memories of those moments my mother and father shared. But when my heart and mind are still, with that sort of silence one gets in the early mornings when the world is not full of countless sounds, and you can hear small creatures move with quiet footfall across the earth, then I can feel the ripples still rolling through my being from that mating.

Ripples of conception

In that silence what I experience is the courage my parents displayed in their marriage. Courage because my mother was a simple country girl, and my father was an Italian immigrant. Or at least he was the youngest child of two Italian immigrants living in London. I also sense an impression of my mother’s unquestioning dedication to my father. I’m not suggesting she was without conflicts. But I believe she was unconscious of them, and so the flow of her life was toward my father. And from my father I feel the enormous force of containment. The force leading him to always hold himself back, to never give himself away, except on very rare occasions. Sex must have been something quite wonderful and tragic for my parents. Wonderful in that my mother’s passion and my father’s containment met. Tragic in that it must have called upon my father to give himself away, and thereby threatened his defences.

The year of our birth is important too. My nativity was just before the Second World War, so I lived my childhood through that incredible period in a country deeply involved in war. Unlike many children living in Britain at that time, the physical events of the war didn’t leave much of an imprint on me. I remember guns going off as a regular background to nights. Rifle shells were easy to find around the fields from the training activities of troops or Home Guard mock battles. Strips of aluminium foil often littered the fields, dropped by enemy aircraft to fool the radar. The sound of the siren warning of an air raid attack made my hair lift and feelings run up my spine, but I didn’t feel any great fear, living as we did, thirty miles outside London. In a way there was a certain amount of entertainment value in what was happening. The gas mask drills for instance were quite ridiculous, as was the drill to get all the children out of the school into the nearby air-raid shelter. This shelter, attached to St. Mary’s School in Old Amersham was a farce. It was s single thickness brick walled building about sixty metres away from the school. Tightly packed, all the children and teachers could just about fit into the shelter, all of it above ground. If the area had been bombed, the shelter offered less protection than the thick walled old school. Being all in one small place, a bomb could have killed us all. The only valuable feature of the shelter was that it didn’t have windows, so there was no danger from being injured by flying glass due to bomb blast.

The other entertainments were the troops marching through the streets in mile long lines, moving across the countryside. I lived in Whielden Street next door to the British Legion hall. This was used as stores for army supplies, and there were often American soldiers just across the fence from where I played in our garden. The British troops were friendly but quiet, but the Americans seemed to carry a completely different aura with them. They were cocky and loud, confident and colourful. It felt to me as a child as if wherever they were, the world was different around them. This was partly that living in a country where all the important items of everyday living were rationed or unobtainable, seeing Americans produce substances such as chewing gum that I had never ever seen before was magical. British people were very grey in comparison. They didn’t laugh and talk as loudly, they didn’t play so easily, they didn’t acquire things with such ease. American comics at that time seemed almost as if they came from another planet. Comparing them with Beano or Dandy, or the text filled Hotspur, led to a feeling that America was full of available BB air rifles, bubble gum, and booklets on personal magnetism and sex appeal. The fact that Superman and Batman are still a part of world imagery, whereas the heroes of British comics such as Strang The Mighty, Wilson the mystic superman, and Desperate Dan are forgotten or only local heroes, shows how godlike the American imagination seemed at that time.

Betty, my mother, was however, much more impressive than the war or the Americans in engraving indelible marks on my soul. I was her first and only baby, and I believe my size and vulnerability frightened her into believing I was always on the verge of death – which of course I was in the beginning. Being only four pounds in weight, suffering jaundice, and not moving about with great signs of life, I believe created some anxiety in my mother.

She was a country girl born in Amersham. Her father was from Irish stock with the name of Banning, and her mother from English parents by the name of Atkins. I see my mother as being an uncomplicated woman without much subtlety, but powerful, strong and very shrewd in her assessment of people. I don’t think she was capable of intellectual thought, but her instincts were clear enough, and one image I have of her is that of a cow, and I don’t mean this as an insult, but as a description. It’s an image that explains to me some of the things she did to me as a child, and how she responded to me.

The mad cow

For instance a cow simply gets on with what is happening to it. If it’s frightened it feels fear and runs. If it is angry it throws its head around and throws its body about in total abandonment. It doesn’t mince about being diplomatic. My mother had that sort of directness. Although she was innocent to the extent that when my father, after seven years of courting first kissed her, she was convinced and terrified that she must have become pregnant. When I was born she related to me in a primal way. The missing eight weeks of development in the womb meant it was difficult for me to digest anything. I was on the brink of death. So imagine a wild cow whose calf doesn’t show much signs of life. It is imperative if the calf is to survive that it get on its feet quickly, that it moves around and looks lively. So when I try to understand the things my mother did, it makes sense that she saw me like this and gave me a good kick now and again to get me on my feet and looking lively. She had no subtlety remember, and didn’t think about things. She simply responded. If I didn’t stand up then I would die, so a good kick might stimulate me into being a bit more alive. I think this was heightened with my mother because she had several heftily built sisters who produced babies weighing in at the magnitude of 9 pounds. My tiny frame of 4 pounds appeared tragically fragile beside them.

The kicks my mother gave me all related to threats of leaving me or giving me away. These would perhaps have been felt as mild parental emotional beatings except that my mother didn’t connect with me easily at birth because of my fragility. In fact my grandmother took over my rearing until she died when I was eighteen months old. This meant that I had not connected fully with my mother or she with me. My grandmother had been my mother. When she died I lost the one who had mothered me, and I felt abandoned, as I had felt at birth.

So at three when I was taken away to a convalescent home because of my sickly constitution, my world fell to pieces. The wound of abandonment cut into me at birth, then at the loss of my grandmother, was ripped open again, and it took over fifty years to put some of the pieces back together again. I wasn’t long in the home, but that I was there at all stabbed a blade of pain and fear into me that left a wound that didn’t heal. The convalescent home shattered whatever frail sense of being wanted I had been able to build in the intervening years. Going into hospital again at six to have my tonsils removed, opened the injury again and deepened it.

What is so strange is how little parents understand about the inner world their baby or child lives in. Perhaps it’s because most of us manage to brick up memories of childhood so it is all but lost except for a few snapshots and what they portray. Without remembering how it felt, the adult has no idea of what they faced and how they dealt with it themselves as a baby. I have to conclude this bricking up, this building of an impenetrable wall against feeling ones early years, has been going on for generations. It must be so otherwise adults could never treat children the way they do. As a group we could never expose them to the tortures involved in some aspects of school, hospital, and in fact everyday life as it occurs in many families.

What lies under the surface?

As an adult I learnt how to knock out the bricks between my adult self and the feeling memories of myself as a baby and child. The horrors behind the wall shocked me as I realised what had happened to me and was happening all around me to other children. It may seem strange for adults with their wall still firmly in place when I say that I can remember being born. I can remember what it felt like to be dying because I couldn’t digest properly – what it felt like to need with terrible urgency that my mother hold me close as if I were still in the womb, and not let me go or put me down until I was mature enough to want to exist apart from her. I can remember that my whole being made a decision at that time to have nothing to do with this new world outside the womb. It was painful. It hurt. It was terrifying. There was no welcome or warmth in it to make me want to get involved in it. Is it surprising then that all my feelings curled up in a ball like a hedgehog to shut the world out? Is it surprising that it wasn’t until I was in my mid forties that I managed to learn how to meet this little curled up ball of feelings that was my baby self, and help it unfold? In doing so I realised that many of the dropouts, drug addicts and alcoholics in our society are in a similar inner state as I was – curled up and trying to withdraw from the world entirely – if only their body would let them. If only the bloody body wouldn’t keep growing and demanding new things from them physically, sexually, emotionally and socially.

As a baby there isn’t anything else in the world apart from your need for your mother, your need to feed, your need to be wanted. There aren’t any neat diversions like watching the tele, going out to a club or bar that is so noisy you can’t even feel your own thoughts and body, taking in enough booze to sedate you, or fucking constantly to keep ones emotions away from what it’s like to be alone. There aren’t any handy tranquillisers to keep your noisy soul at bay. There aren’t any dealers selling dope. As a baby you have no bank account from which to pay an unwilling mum to induce her to provide your emotional needs, to make her stay with you instead of farming you out to a child minder.

If you have ever fallen in love – really up to your eyeballs in love – and the person you want and need to be with desperately is completely indifferent to you, then you begin to understand what it feels like to exist as a baby with its tremendous capacity to want love. You begin to understand what it is like to know you are on your own, that you are simply a lodger in the house. The question the baby asks with its whole being is “Do you want me?”

Mum – I love you!

If the baby could put its feelings into words it would say, “I don’t want to hear all these excuses about ‘Yes mummy loves you, but now she’s going out with her friends, or she needs time alone.’ That’s all bullshit. If you love someone you want them to be with you wherever you go. My love for you isn’t a head-trip. It isn’t a bloody quiz. It isn’t a game of the month on TV. It’s ME. It’s my whole life. If I am going to give you my love I want to know – I want to KNOW – I want to know beyond any doubt, whether you’re trustworthy – whether I can trust you!”

If you think that is what someone would feel who is totally dependent, you’re right. The baby is built, deep down etched in, to be totally dependent. It’s called a survival instinct.

When I was meeting such feelings and pondering if they were a form of sickness or a natural situation, I was lucky enough to watch a nature documentary on British television about a herd of elephants. The film centred on a baby elephant that had become separated from its mother and the herd. The separation had come about because the baby had got stuck in deep mud at the edge of a waterhole. Hyenas were not far away, and the baby knew instinctively that if it cried out for help it might attract the hyenas, which meant death. So it remained silent but desperate, because it would die anyway trapped in the mud. Then it heard a group other than its own herd nearby. A dominant female always leads such herds. The baby called and the herd came, recognised the baby didn’t belong to the group and started to leave. The baby cried so desperately the dominant female tried to pull the baby out, but failed, and the group started to walk off. The baby called again, and this time the group succeeded in pulling the calf out of the mud and adopted it.

The point is that certainly in the past, and still today in many parts of the world, abandonment means death. The greatest and most prominent drive in a baby animal is to stay connected with its parent or group. If it doesn’t it will almost certainly die. That instinct has been built into us as vulnerable animals for millions of years. The baby cannot help but feel that imperative.

When I met the feelings involved in being apparently abandoned in the convalescent home, for six weeks I couldn’t function normally because the emerging emotions and states of mind were so strong. If you have never had an actual experience of this nature it may not be possible for you to understand or believe. But I will try to explain.

Remember that what you take for granted as an adult is not operative in the baby and young child. For instance a sense of time is something you learned as you gained the ability to speak and grasp certain concepts such as morning, midday, evening, a new day, minutes, hours, etc. Before that you lived in a timeless world without beginning or end. A day, even a minute is eternal. So when a mother says, stay there I will only be five minutes, to the mother that seems very reasonable. But to the child it has no meaning whatsoever, and the length of her departure is only measured in terms of its own inner feelings. If it misses its mother, the pain is eternal. Perhaps that’s where the concept of Hell originated.

Also, from the drives and needs a baby and young child operate from, it doesn’t compute that a mother would let her baby be separated from it. Remember that it has the imperative to stay near, to go everywhere the parent or family group go. So just as we can add 2 and 2 and arrive at 4, but it doesn’t compute if we say it adds to 5. So with the baby it doesn’t add up that the mother would leave it anywhere. The baby’s drive is to stay close. If the mother and family don’t match that, an extraordinary confusion grows in the baby’s feelings. It isn’t that the baby can think this out. Like any young animal, it responds from the fundamental information built in, such as instincts. So what it arrives at in an intuitive or instinctive way is that it isn’t loved. It feels it is of no value and has been abandoned. This leads to an enormous internal kick that stimulates other instinctive responses. There is murderous rage on the one hand, and a tremendous desire to please the mother by doing everything that would make one acceptable and lovable. When older children exhibit either of these two responses by murdering their parents, or continually placating them by behaviour or gifts, such behaviour probably arises from this level of feeling response.

Hit the ground running

The instinctive or automatic responses that follow after that are complex, in that the baby can go in one of several different directions. But one of the first actions is to seek the mother or try to attract her attention. Like the elephant, the baby may cry out. But also like the elephant, the cry will only go out if there is hope of response, not if the child feels hopeless and vulnerable. If succour – a breast – is offered, at first it will not be taken unless it is the mother’s. But if the mother fails to arrive, the next stage is to accept the breast that is offered, while continuing to hope for and seek the mother. In adult behaviour this can lead to a person taking multiple lovers while trying to establish a safe relationship with one person.

Another possibility is that because the baby is not getting nourished by knowing deep down in its guts that it is wanted, it may develop a compensatory inner life. It may turn inwards and find an image – such as Jesus, God, an imagined person or a dead relative – from which it can receive unquestioned love. Many of the classic forms of prayer or meditation can be seen as this process in action. The person closes their eyes and creates an experience of bliss or transcendence out of their own emotional and mental energy. In the end this is a sort of auto-stimulation, but it has a very real advantage if the child – or adult – doesn’t get nourished by external love. The internal image enables the child to continue its inner psychological and emotional growth without an external source of love. For the adult it enables them to continue living in what may be harsh or impoverished external conditions – for instance without a sexual partner. The inner compensatory figure or image may later be difficult to give up. After all, external people have proved themselves unreliable with the child. But the change can be made from an internal to an external love.

I believe all the reactions described happen on a purely reactive or instinctive level, and are almost entirely unconscious. As happens when we have driven a car for years, most of the things we do are not noticed, as they are so deeply habitual. What fascinated me as I discovered them in myself and others, is how level after level of survival reactions are built into us.

I was recently reading an old book by Tony Buzan and Terence Dixon – The Evolving Brain – in which they describe the work of professor Luria. Luria defined that the brain operates on system functioning rather than on area functioning. He described this using the example of the respiratory system. The lungs are usually enabled to inhale and expel air because the large muscle of the diaphragm does most of the work. If the diaphragm is made inert with an injection, the muscles in the ribs – the intercostals – take over. If the intercostals are also put out of action the muscles in the windpipe – trachea – take over.

Similar actions or fail-safe systems are built into the body at every point, particularly noticeable in the circulatory system. What Luria was pointing out was that the brain, like the body, has interconnected activity. Just as the lungs do not work simply through the action of the diaphragm, so the brain doesn’t enable us to see or speak with one area of its lobes. What I have seen in regard to levels of response in connection with survival of our identity seems to have a similar basis. If one level doesn’t work, or doesn’t meet with the necessary requirements, then another level of reaction arises. I think this is particularly true regarding birth, childhood and parenting – both giving and receiving. With my mother for instance, my premature birth triggered in her quite a different set of responses than if I had been a healthy full-term baby weighing nine pounds like her sisters babies. Intuitively, I feel the way my mother behaved toward me was based on experience that she didn’t gather in her own lifetime. It wasn’t personal knowledge, no more than the way a bird builds its nest is personal knowledge. I have the view that her actions came from a collective experience gradually gathered through untold generations, and through unimaginably vast periods of time. Because my birth, with its pain and stress, both on my mother and myself, had pushed us both beyond the resources of our personal life, I believe we both became wise from this collective wisdom.

The inner language

Something that started me thinking along these lines was a dream I had in the early eighties. In it I was walking down a sloping cobbled road in Italy, a country I had at that time never visited. I knew in the dream that I was there to learn the language. The dream didn’t seem particularly important, but at the time I was exploring dreams by taking time to allow spontaneous feelings, memories and associations that might occur in connection with the dream. As soon as I started exploring this dream the connection with Italy was obvious. My father was full-blooded Italian although born in London. So this dream had something to do with my family background. I didn’t understand what learning the language referred to, because I had never learned the language, nor had my father. But as I allowed feelings and associations to arise something quite remarkable happened. Lots of different pieces of my life and the things I experienced in myself and in connection with my father came together, forming a larger picture, a greater understanding. I was about forty-four at the time of the dream, and up till then had not voted. Politics, or involvement in any other mass organisation was something I avoided. I didn’t know why. I had always taken it simply as an expression of my personality, perhaps of my ideals. What emerged more and more clearly as I entered the dream, was that my father had passed on to me a deeply etched message that any such organisations were dangerous, and this was why I had avoided involvement.

At this point I couldn’t see, and I didn’t understand, how this message had been passed to me. My father hardly ever talked to me. He had certainly never talked to me about such issues, or impressed on me with fervent tone that I must avoid organisations. But the process behind the dream was still unfolding, allowing deeply unconscious material to surface and be known. The bricks were coming down between me and my child self, and I saw with deep awareness that my father hadn’t needed to speak to me about these things, his every small mannerism, his relationship with other men, his whole approach to life, had been telling it to me all the time. It had been a purely non-verbal communication. It was as deep and as soundless as the communication the mother bitch gives to her pups when she licks them clean after birth, when she picks them up in her mouth, when she gives them her milk. So my father had passed his soul to me in silence and in quiet union, and my own soul had understood in its own silence. Now, out of that silence my soul was speaking to me and unfolding what it had learned of the language of Italy.

The way I had learned from my father was the way all mammals learn from parents, by a sort of mental osmosis of behaviour. The fox has no words to use in passing on to its offspring the lessons of survival learnt – how to hunt for instance. But the lessons pass down generation after generation because mammals can absorb enormous amounts of information non-verbally. A wonderful study of the African wild dogs showed exactly the value and wonder of this. The dogs had been wiped out in a large area and attempts were being made to reintroduce them. A documentary film showed two packs of dogs. The one pack were established, and had arisen from an unbroken line of descent and social relationship for thousands of years. The second pack had been reared in captivity and released in the wild with some support. The descended pack showed enormous social skills in acknowledging and supporting each other’s rank, in working together to hunt, in feeding the pups and mutually caring for them, and in sharing food with those who stayed to care for the young.

That ancient wisdom

The released pack didn’t have any of these skills. The information was not being passed on to them from a previous generation. They couldn’t work together. They fought amongst themselves instead of respecting leadership. They didn’t share food but fought over it. They all quickly died. The unspoken wisdom of generations had not been passed to them. They had no survival skills. They died.

Similarly a study of an elephant reared in captivity showed the same sort of story. When the reared elephant met herd elephants, it didn’t know how to greet them. It didn’t know how to relate within a group. It didn’t know how to care for the young or rear its own young. Although it had the shape of an elephant, it wasn’t really an elephant. An elephant is not simply a particular body shape. It is also a set of responses honed to enable it to survive within its group and environment. This extra dimension, which is so often overlooked, especially in human babies, is passed on from generation to generation wordlessly. It is automatically absorbed in babyhood through a sort of recorded impression of behaviour in parents and family.

The experiments in Japan where macaque apes were fed rice, showed this aspect of learning in detail. Imo, a female of the troop, learnt to scoop up the grains of rice the apes were being fed on a beach, carry them to the sea, and wash off the sand grains. This was completely new behaviour for the troop of apes. Soon however, other troop members learned how to wash their rice through seeing Imo do it. As new babies were born they adopted the behaviour until it was common practice for the whole troop. Hundreds of years later the troop could still be practising the wise responses started by Imo, though she is long dead. But the behaviour of the troop taken as a whole has been developed from many such great innovators as Imo, and passed from generation to generation by living example, absorbed wordlessly even while at the breast.

So I do not see the collective wisdom my mother and grandmother exhibited as something mysterious or ethereal. It is a visible and living thing passed on through a sort of love that enables the baby and child to copy intimately the behavioural responses of parents, other people, and even animals it loves. Through this love we absorb another being into ourselves. We absorb from them even what they may not be aware of having themselves, because most of their behaviour is unconscious. Their most meaningful and ancient self – a being and self that did not begin with birth and does not end with death, is absorbed if we have loved and are loved.

If one grasps this fundamental fact of how we learn, and how wisdom is passed from ancient times through the living, then I think it becomes obvious that not only is there a family tradition of passed wisdom and survival skills, but there is also a national or cultural behavioural pool. We are now used to thinking in terms of a genetic pool, with its richness or limitations because of the smallness of the group. We need also to recognise that there is a behavioural pool which can also be rich or impoverished, and we need to be aware what is being taught at this level, and whether it strengthens or weakens a child, and thereby society, for the business of life and love.

What my father passed to me in this way unfolded in a most profound way. To give an impression of what it was like to experience this I can only say it was as if my father had in my childhood given me a cassette with music on that was all the time influencing my life. But I had the volume turned down, so I was never consciously aware of what the music was, or my feelings responding to it. Working on the dream turned the volume up to the point where I was deeply aware and responding. The similarity between the package my father gave me and a music cassette or CD also lies in the latency of the music on the cassette. On the cassette the music is simply a series of magnetic impulses or digital messages. Only when the cassette is put on a player of some sort and the produced music is listened to does it become a human experience one can respond to, think about and perhaps express verbally or in other ways. What was on the cassette leaps into three dimensions. This is especially so if the cassette has video recordings on it. The signals on the cassette are not images. But when we play the cassette we can SEE what it held latent. So the package my father gave me opened when I ‘played’ it, and I could ‘see’ what was latent in it.

I don’t think that is surprising. After all, our brain is doing it every moment as we take in signals of light or sound and translate them into impressions we can see or hear in a meaningful way. So when I explored the dream a massive amount of information opened up and I ‘saw’ what my father had given me through the love I had for him. It was something his father had passed to him, and so back for generations. It had arisen in our family from a time of religious and political persecution in Italy. The central message passed on through each generation for perhaps hundreds of years was, ‘keep your head down’. This was why I hadn’t voted or got involved in any form of organisations or public work.

As the message opened I could see why. During the period of persecution, any sign, any thinking or action that was in opposition to what was thought or decreed by the religious and political establishment was rewarded with death. But it wasn’t necessarily death of oneself. Often ones children were slaughtered, and ones fields and crops burnt. This was more awful to us than personal death. Our vine had been cut off at the roots. Our family vine could no longer grow if children and land were destroyed. Therefore to survive in those times my forbears had kept their thoughts and beliefs to themselves. They had lowered their eyes. The men had burnt inside but kept quiet. It wasn’t a good policy even to tell neighbours what one really thought. So this led to a deep secretiveness about who one was. In the end it might even be that one lost sight of oneself in this subterfuge, this deadly hiding and waiting.

I heard the shouts of my ancient family echoing down through the centuries. ‘Just because someone calls himself a king doesn’t mean he’s a man. He can’t even fuck his own wife, yet he wants us to bow down to him. And if we don’t he has what he calls an army, who are paid thugs, to kill us. The bastards even took our religion and turned it into something to chain and frighten us with through death and hell.’

So this wealth of experience and passion from my mother and father, from my ancient forebears, was all part of my birth. I was born not only into a body, a place and a time, but also into a great pool of family and cultural experience. Discovering it led me to connect with the world much more realistically than I had previously. The difficulties and strengths of my life now have a context that I never knew previously.

The collective memory

The long diversion was to explain what I gradually uncovered about the depths of collective memory that my mother drew on in some of her reactions to me as a tiny premature baby. Sometimes I call what she did the ‘one tit’ theory. What I mean is that if a child is healthy and strong, the mother feels her child has a good chance of survival. Without the constant fear that her child will die, the mother simply gets on with feeding her baby. In this case the mother is all the baby needs. This is the one tit, or one mum situation. But if the mother is constantly anxious because the child is sickly, then perhaps unconsciously she works out ways her baby can survive. What if she herself dies, what will happen to her child then? It is so weak and needy it couldn’t help itself, so she has to knock survival traits into it – reach out for other tits if the one tit or source of sustenance disappears – don’t depend on the one mother but stand on your own feet. If the shit hits the fan, don’t rush around looking for your mother to help you, she might not be there, so when your feet hit the ground run for cover yourself, go for whatever protection is around.

This ties in with what I have already said about my mother as the cow who kicks its calf to make sure it will get up and move around to show signs of life. Once anxiety switches on in a mother it does strange things to her relationship with the baby, and what she discovers in herself. When my son Leon was working for a year prior to entering Cambridge University, he met people who owned wolfhounds, and often walked the dogs. I went with him a couple of times. The dogs were kept in a large pen, but one of them, a bitch, was kept in the house because she had recently given birth to pups. When we went to the house to let the owner of the dogs know we were going to walk them, the bitch came to the door to look at us. As soon as she saw we were strangers she rushed back to her pups to check they were okay. Then, for the short period we were there she continued to come and look at us with obvious tension, and then run back to check her pups.

If one observes animals for any length of time, it is soon obvious that anxiety is one of the most frequent responses in their daily life. From the amount of drugs taken which tranquillise the system against anxiety, such as alcohol, nicotine and the mass of prescribed medications, humans meet anxiety as much as or more than the rest of the animal kingdom. What was interesting about the wolfhound bitch was she so obviously lived out her natural anxiety as part of her way of caring for her pups. People, especially women with babies, often don’t allow themselves to be so direct about anxiety, or they feel terrified of feeling afraid. It then becomes an illness.

My mother’s anxiety lasted throughout my youth and expressed in ways that left psychological scars that deeply changed the directions I took in life. As an example, one Spring when I was about six, I had walked home from school for lunch. I hated school meals and so walked back to our next-door neighbour’s, Mrs Spilstead, who fed me while my mother was at work. There was only one other boy who also walked home at lunchtime. I remember his name was Brian Spencer. On that day we met up on the way back to school while walking along Whielden Street where we both lived. There was no problem in crossing Amersham High Street in those days, as there were so few cars about. At the beginning of School Lane there used to be a wonderful open meadow rising up a steep hill to The Rectory. Now it has buildings at its foot, but then there were only giant horse chestnut trees and a huge expanse of grass. As we were passing, the thousands of Michaelmas daisies in the meadow were too much, too many, too glorious to ignore. We climbed up the bank and into the waist high grass to pick the daisies. It was our plan to give them to our teacher. On arriving at school however, we must have lingered too long in Rectory Meadow, as all the children were in class. The massive oak door of our class, facing directly on to the playground, was closed and formidable with its large iron studs pointing out to us. We stood looking at it for a while, daisies drooping in our hands. It seemed to me too difficult to open that massive door and face all those enquiring eyes. So I thought the best plan was to play in the Recreation Ground across the road from the school until playtime. Then we could mingle with the children and enter class without crisis.

Beyond time

I don’t know what happened to the daisies. I do clearly remember that we got deeply involved in catching sticklebacks in the small river – the Misbourne – at the end of the Rec as we called it. When playtime came our classmates flowed over the Rec and watched us for a while with our arms deep in the scented Misbourne. I don’t know why, but no thought of school ever came into my mind. Somehow the river, the fish, erased all concepts of school and of time. I have no recollection of purposely setting myself against going back to school. It simply never occurred to me that I needed to. The river and the willows along its bank were all. Even when the children reappeared again the spell wasn’t broken. The information never even got anywhere near to telling me that time had passed and I would be expected to return home. For those hours I had returned to a younger age where there were no goals, no appointments, no expectations, only the moment.

There are several indelible images of what then happened. One of them is of myself, still with arms into the river, bent and intent, suddenly aware that a shadow had fallen over me. It was my mother. I was so pleased to see her. I tried to share the wonderful river, but I was pulled away.

I can remember the exact place where the next image was engraved into me. My hand was being held firmly by my mother as we walked along Church Street, on the left hand side before getting to what used to be Goya’s scent factory. There is a blank as to what had been said before that. I know I had been questioned as to why I hadn’t returned home on time, and why I had missed school. I had explained as well as a six year old child can. Suddenly my mother said, “You hurt me. Now I am going to hurt you.”

She never explained how I had hurt her, but I suppose she meant she had been worried sick when I didn’t return home at the usual time. Then followed the third ingrained image. My mother took me home, undressed me, bathed me – we had a large zinc bath then which had to be filled from saucepans and placed in the middle of the kitchen floor. She then dressed me in my Sunday best clothes and told me I was going to be put in a children’s home.

I had not known my mother to make threats she didn’t carry out. So I took this as a statement of her plans. Remember that I already knew the pain of the convalescent home, and behind that the sense of being motherless at the death of my grandmother. There was already a pit of terror in me called ‘Abandonment’. The threat of being thrown to that monster again tore me open. I clung to my mother begging her to keep me, and the scene fades in my memory as I cling to her begging and sobbing.

The result was that from then onwards I cut my mother out of my heart and cast her aside. I would no longer sit next to her or treat her with respect. I would no longer trust a woman with my love. I started calling her ‘an old cow’ – another way of helping myself kill out my feelings for her and my emotional dependence on her. Being that independent turned into a wonderful strength, but a terrible weakness. I was much more individual than most boys. As a young man called into the armed force for national service, I was far less prone to homesickness than most, and not given to depending on a girl friend to help me feel wanted. Even at forty, I had been married for years without ever knowing what it was to have an emotional bond with my wife. It took my second marriage to show me the pleasure, and reintroduce me to the pain, of actually learning to love someone again.

On the positive side however, the wisdom of what I have called the ‘one tit’ or ‘multiple tit’ theory, fostered the ability in me to be independent and helped me develop survival skills. Having met people whose mothers expressed their anxiety in a smothering way, perhaps by trying to make their child totally secure and protected, I am glad my mother had the instincts of a wild cow and gave me a hefty kick now and again to get me on my feet and teach me to growl at the world and occasionally bare my teeth. Nevertheless, it was a hard lesson.

Birth revisited

The memories of my own birth were not the only ones I was privileged to witness. I worked for over twenty years as a psychotherapist using a technique that encouraged and supported spontaneous expression of movement, fantasy and feelings. I called this Self Regulation, or more recently LifeStream. I was helped to define this approach partly from Carl Jung’s description of the techniques he used to enable people to find meaningful communication with, and release of, their previously unconscious inner life. He encouraged people to use their hands to fantasy, and also to dance or draw. He personally used a process of spontaneous voice – speaking to oneself. My approach to these types of phenomena was widened by descriptions of the process as used by other people such as Wilhelm Reich, but especially from other past or present cultures.

This may sound as if I set out to explore these techniques as a professional. This is only true in a small degree. I felt desperately unhappy and depressed, with awful psychosomatic pain for years of my life. So my search was out of this desperation. It was out of my need to find ways out of the misery.

Overall these approaches, as varied as the original Pentecost, Subud in Indonesia, and Seitai in Japan, show that if one can learn to drop conscious direction of ones body and mind, and become open and receptive, what was previously unconscious can emerge and be expressed through mime, sound, and vivid fantasy, that is often as powerful and convincing as a dream. In fact I believe it is the same process at work in these experiences as is functioning while we dream. This process, which leads to fantasy and creation of some form of drama or story line, is fundamental to us.

Unless one has experienced the power and immediacy of this release of previously unknown and unexpected material, it is easy to think that people create a sort of illusionary fantasy, something like a daydream. When the individual works well with their own receptiveness of body and mind, there is, however, an observable and developing experience of memories and insights that gradually bring a radically enlarged perception of oneself and ones life history. This is very different to the sort of wandering we do in daydreaming, with very different results. The power of these experiences is often enormous, with explosive or deep emotions. What is experienced, if met in a way to explore its foundation in the real issues of ones life rather than idealised hopes or goals, leads to a piecing together of the powerful formative experiences in ones life. Out of this arises the ability to further ones growth, and from the gathered insights, produce changes in habits and fears that had bound one for years.

Jung called this process the Transcendent Function. This name arises because overall the process produces an observable movement toward greater wholeness of the personality. It also eventually leads to a transcendent experience. This action, described by many other people than Jung, and in many different cultural approaches, was most likely seen as a religious or spiritual process in the past because of this tendency toward wholeness, and the way it leads toward a new life transcending the old.

During this work I often watched and was involved in people experiencing what appeared to be direct memories of being born. This is quite different to the experience of birth as a psychological function. What I mean is that if one watches dreams for any period of time, the subject of, or the experience of, birth, occurs to most people fairly often. As a dream theme it may not be about the event of ones actual birth. It depicts the emergence of some new part of ones personality. For instance a woman who had recently ended a ten-year relationship dreamt she gave birth to a girl child. When she explored the dream and entered into the role of the baby, very distinct insight arose that the image was about the change in herself, the new and still vulnerable part of her that was emerging now she had found the courage to start life in a fresh way. This sort of psychological birth into a fresh start, or a new venture, is quite different to meeting the memories of ones own birth. If one has recovered such memories it appears strange and awful that medical practice, educational policies, general social behaviour, appear to be completely blind to the immense importance of the birth experience in the development of each of us. I said earlier that I remember what it was like to feel myself on the edge of death as a baby, and to be constantly starving. Feelings of that intensity do not simply melt away as one ages. They etch indelible responses into ones emotions. They set patterns of behaviour that calcify in later years.

Before Abraham was – I am

Many adults think of babies as incapable of intense learning or conscious response to anything. Certainly if one remembers birth or life in the womb, there is no sense of being a conscious person as occurs later in life. There is no sense of identity in the way we achieve it in adulthood. But we do have extremely sensitive receptive faculties and responses. Even a tree or a plant can be seen to respond very quickly to light or water, and a baby has an immensely more complex nervous system and brain than a plant.

Talking about this complexity of our nervous system, but particularly our brain with its ten billion neurones, John Rader Platt says, “If this property of complexity could somehow be transformed into visible brightness so that it could stand forth more clearly to our senses, the biological world would become a walking field of light compared to the physical world. The sun with its great eruptions would fade to a pale simplicity compared to a rose bush. An earthworm would be a beacon, a dog would be a city of light, and human beings would stand out like blazing suns of complexity, flashing bursts of meaning to each other through the dull night of the physical world between. We would hurt each other’s eyes. Look at the haloed heads of your rare and complex companions. Is it not so?”

Somehow we get a completely reversed picture of what a baby is. Most people consider an adult far more capable of learning than a baby. Yet an adult has absorbed many traits that have already defined and restricted their reactions. The adult has learned to repress emotions and hide their own truth – perhaps even to the point of forgetting it themselves. The baby hasn’t learnt any of these defences and limitations. The world of experience is completely new and unfiltered. It isn’t wearing a bullet-proof jacket and leggings to protect it from the emotional and physical hits that come its way.

It must be observable to all of us that a woman who has had a destructive love affair, finds it harder to relate to a man openly if she dares to enter another relationship. It isn’t that the woman has sat down and said to herself – “I was badly hurt in that last relationship. To avoid getting hurt again I am going to be very cautious and guarded. I will react nervously to any move a man makes toward me.” She doesn’t need to do this. It is built into all of us as a fundamental learning process that if something hurts us we react without thought to it next time it confronts us. When the baby is hurt it learns a reaction. It doesn’t need words for that reaction, and as that baby becomes a man or woman, the reaction shapes the way they deal with the events of their life and how they think about their experience.

There were several powerful reactions I learned from my own birth. I discovered the first on the list because in my early forties an attitude that had been a part of my character all my life became troublesome. I had always been something of a loner, but in my forties the lack of any drive to get involved in what was going on around me became troublesome because it conflicted with the work I was doing. I was teaching, and the desire to withdraw and avoid involvement was intense. When I explored this using the technique described above, I was amazed when the process led to a gradual regression back to the moment of birth. I want to make it plain that I am not suggesting that I somehow went back in time to relive my birth, or that I replayed a sort of tape recording of my birth events. What I did meet was the pattern of feelings and reactions that announced themselves as having arisen at the time of my birth.

In the process of self-regulation the body is often powerfully involved through its spontaneous movement, and such movements are commonly accompanied by profoundly deep emotions. In this experience my body curled up as the emotions connected with my desire to withdraw unfolded. But it wasn’t the physical activity that I became immersed in, it was the enveloping awareness of a deep need to be wanted. I sensed myself as a sentient but not self-conscious being, and an observing part of my mind took this in. I was newly born and an instinctive desire to be held and wanted filled me. At that time I was not aware of any difficulties. If there were any, or if there had been any, they were of no consequence if I could be held and wanted in the way a loving mother wants her baby. I felt sure as the observing part of me watched this, that this was a deeply rooted instinct. I believe all babies have this natural impulse and expectation to be received and wanted. When I was in that state of regression, I didn’t feel as if I was imagining what a baby felt like – I WAS the baby. There was no sense of being the adult Tony other than an observing point of awareness. I was a scrap of life informed by something that felt like life itself, vast and dark, of which I was an integral part. If there was any crying, it wasn’t I who was crying because as yet there was no ‘I’. It was life, with its awful sensitivity and capacity to feel that cried. What expected to be held and wanted was this dark and vast life of which the baby me was a part. We call that instinct, as if instinct is some sort of encoded message. But as the baby it didn’t seem like that. It seemed that out of the dark hugeness of my awareness I knew I should be welcome. When there was no welcome, no warm mother to hold me, only further difficulties, my whole being reacted. A desire burned in me to withdraw into the darkness, to get lost back into the hugeness and not feel the torment of this experience.

At that time I felt like an egg, like a chick in the egg. Somehow my shell had been taken away and all I wanted was to curl up and not have to be alive. Events were not offering me what my instinct had led me to expect. Without any certainty of being wanted, I was exposed, alone and vulnerable. There was nothing for me to unfold for or want to live for.

Prior to this experience I had watched a documentary on the hatching of turtles on a beach. They were all impelled to run toward the sea, and if they made it they were comparatively safe. But on the way the seagulls swooped and ate many of them. As the baby I had no impulse to run for the sea. I was too aware of the dangers to want to move. I didn’t even want to be without a shell. There was no way the baby me wanted to unfold and participate in the adult life of Tony. But as Tony, observing this part of myself that had decided right at the beginning not to get involved in the difficulties or possibilities of life, I realised I had to find a way to induce it to change. If I did not manage this, a whole spectrum of my energy and potential would be missing.

A dialogue began between my adult self and this curled up ball of feeling deep at the core of me. I tried to convince it that I needed the enthusiasm for life that it had withdrawn through its retreat from experience. Its only response was to curl up tighter and set itself against any possibility of opening. I could see that the baby in me had a great fear of being attacked, because it felt so unprotected due to not having a sense of connection with its mother. But the image of the baby turtles appealed to it, and its response was that it didn’t want to run because it would get eaten. However, I suddenly realised that meeting the risks of life didn’t necessarily heighten vulnerability. So I communicated to my baby self that lying curled up as it was, made it more open to attack than if it ran. At least if it uncurled and ran it would stand a chance. This was so obvious once pointed out that I could sense a swing of feelings in the baby. It was ready to begin being a part of my life now in an active way. And this marked a major turning point in my life.

Life before birth

Remembering ones own birth, and watching as other people encounter their own memory, suggests what modern quantum physics is beginning to appreciate, that awareness is not something that only occurs in an animal after birth. In some degree it is present in everything at all times. It may even be a fundamental fact of the universe. (1) Certainly thousands of people have now been able to remember their own prenatal life and the events of their birth. But they particularly have recall of the feelings surrounding their birth, and the long lasting influence it had on adulthood.

What I have gathered of this as someone who has gone through the experience of being a union of sperm and ovum, a foetus and a baby delivered out of the womb, is that in some way I experienced it all. I don’t mean Tony was present as a sort of phantom personality. I do mean that when Tony as a personality came on the scene, I was the recipient of all the unconscious influences the passage through the strange and wonderful worlds of conception, gestation and birth left with me. In turning self-awareness back on its roots, the recorded traces of my journey are available to me. It is not available as distinct and formed visual or vocal impressions, the sort most of us call memory, but as subtle feelings and reactions, explosive emotions and antipathies. It can be ‘played’ just as the information my father passed to me could be played.

From these I have learned that life in the womb is a time of connection. There is little or no sense of separation, or existing as a distinct being. It is only looking back on this from the perspective of self-awareness that one can analyse the state at all, or put words to it. At the time there is no centre of perception that can say ‘I see’ or ‘I feel’. There is simply existence and experience. There is no feeling of a marked boundary between oneself or ones mother, or ones own existence and that of all other living things. If the experience can be described at all, then perhaps it is like being a finger on the right hand. As that finger you have a distinct physical form. If you had eyes and looked out from them you would see other fingers that were distinct and separated from yourself. Your movements and experiences would be different from theirs. Your experience gathered in this way would lead to the conclusion that there was no connection between you and other fingers, even if you have arisen from a common source. But if you could turn your awareness inwards and travel down into yourself, you would discover that there is no distinct separation from yourself and the hand, from yourself and the body, from yourself and the other fingers, eyes and organs. In fact you are one and the same body expressing its different functions and needs. You would know that your pain or pleasure is known by the whole body in some degree.

The unborn baby lives in this world of connection or union. There is an emerging sense of difference as the baby matures and nears birth, but the sense of unity is still there and remains after birth, gradually diminishing as language is learned and identity emerges. The feeling of difference has its roots in such things as the experience of ones own heartbeat and the pulsing pleasure this radiates throughout ones whole system, and how this varies from the pulsations arising from the mother’s heartbeat. When the two rhythms cross each other and beat as one, the flooding pleasure increases. Maybe such heightened pleasure is even the roots of love, the hope that two hearts can beat as one, the desire to feel in union with another identity, another system of beats, responses and rhythms.

What I am calling the roots of love can at times develop in the unborn baby into feeling supported or undermined by the attitudes and emotional state of the mother. The baby does not have a personality that can feel confident or anxious, but it is nevertheless capable of experiencing pain and pleasure, well-being or fear. The baby feels the mother’s emotional state. There is nothing mysterious about this. It isn’t necessarily mystical or strange. We don’t think it mysterious if we walk into a room and immediately sense tension. Hundreds of small cues tell us what is happening, and we react to that with our own feelings. Perhaps we ourselves feel anxious and tense. So too the baby, a life form with enormous intelligence, sensitivity and feeling response, can pick up the cues given by the mother’s physical reactions, her heartbeat, breathing and quality of movement and even voice. The quality and quantity of the mother’s pain and pleasure, wonder or defeat, love or anger, will in some way contribute to the baby’s development and later tendencies.

These are not simply my own ideas. Dr. Thomas Verny and John Kelly, in their book The Secret Life of the Unborn Child, show the possibility of degrees of consciousness existing in the unborn baby from the time of conception. The Journal of Experimental Psychology published a report by Dr. Spelt on how unborn babies learned to kick in response to an applied vibration. Dr. Michael Lieberman showed how an unborn child grows emotionally agitated, shown by its heartbeat quickening, each time its mother thinks about smoking. Smoking lowers the oxygen in the bloodstream, so causing an unpleasant sensation to the baby.

Obstetric physiologist, Michelle Clements has shown that the unborn child has musical preferences. The foetus doesn’t like rock music for instance, but enjoys flute music or gentle sounds. Dr. Dominic Papura, through measurement of the baby’s brain waves while still in the womb, discovered that not only does the baby have periods of waking and sleeping, but while asleep it dreams. And although there is as yet no conclusive research on this, Dr. Verny believes that many mothers experience the baby communicating its needs to the mother in her dreams.(2)

I remember – I remember!

Stanislav Grof, a European psychiatrist who witnessed thousands of sessions in which patients were given LSD to help them explore their psychological difficulties, found that it was common for patients to experience what it was like to be in the womb. Grof originally thought these were some sort of fantasy stimulated by the drug. The cases were all recorded however, and patient after patient described similar experiences, and gave details of events that only a deep knowledge of embryology would have made possible. The details of circulation in the placenta, the internal environment and its sounds, and even biochemical changes taking place, were all described by patients, along with the more obvious information of how their mother felt, and what happened to her while they were in the womb.

Grof tried to find out if these assertions linked with external facts, and questioned mothers and family. In many cases he was able to verify what the patient had discovered and described while remembering their prenatal and postnatal experiences. Some of the people involved were themselves biologists, psychiatrists and psychologists, as all staff had to undergo experience of LSD as part of their training to better support patients.

First and foremost, the forming baby is aware of being wanted or not. We are not speaking here of passing moods of anxiety in the mother about whether she will cope or whether she ought to have had the baby, but the deep down rejection of the developing being she carries inside her. The mother of a newborn baby, who turned its head away from her offered breast, admitted to the doctor that she hadn’t wanted the baby. She had it because her husband wanted a child. When put to the breast of a stranger, the baby fed happily, but continued its refusal of its mother. Studies of such babies as they grow, show that as children their sense of rejection influences them in their adult life. They find it more difficult to make friends, and spend much time alone. Conversely, babies actively talked to and loved in the womb, show greater tendency to be happy and more sociable as adults. They also have less physical illness.

Our memory also starts in the womb. Boris Brott, conductor of the Ontario Orchestra, had been mystified by his ability to know the flow of pieces of cello music without seeing the score. When mentioning this to his mother, who was a cello player, she asked what pieces they were. The mystery was solved when all the scores were ones she had played while pregnant.

For mothers who form an emotional link of communication with their baby during pregnancy, holding the baby in their arms after their birth is not the meeting of strangers, but an established love continued.

As the unborn baby I need to be loved in the womb and when I emerge. To the baby, whoever loves it is its mother, as shown by the baby turning its head away from its mother’s breast. What we call love, the deep committed connection, the empathic understanding of what the baby experiences and needs, is as vital to the baby’s development as food. My mother, through her anxiety could not supply the amount of love I needed, but my grandmother loved me with a fierce passion that had in it the power and courage I needed in facing my feelings of being on the edge of death for so long. My grandmother was my mother, and when she died I spent years unconsciously looking for that quality of love again, feeling that my natural mother was simply a woman looking after me.

I see this as a clear indication that a baby may need more than one ‘mother’. The old fashioned nanny is still a wonderful thing, if the nanny is a woman who deeply loves the baby and understands its world. Emotional connection is deeply important, and a woman who feels she can leave her baby in the care of a baby sitter or child minder whom the baby hasn’t chosen as its love partner doesn’t understand this. Such practice is as awful as suggesting that because we are going to be away for awhile, we will hire a woman/man of our choosing, to be a sexual partner for our wife/husband until we get back. In many ways the baby is much more choosy than the adult about who it is going to relate to and trust itself with. So to pay a surrogate mother is as bizarre as the hired sexual partner.

At birth the baby needs to be wanted. It expects to be welcomed and connected with in a very primitive way. I once sat in on a lecture about sociology and infants in Third World countries. In the following discussion there was some talk of bonding and I suggested how much the baby needs this. One woman said, half under her breath, “How do you define bonding”, as if it were some intellectual inquiry.

To the baby there is nothing intellectual about it. It needs as ferocious and physical a love as the wolf bitch gives to its pups. It needs the same sort of growl in the throat of the mother if a dubious stranger gets near. It needs the wonderful panting pleasure of giving ones tits. It doesn’t want the poison in the sort of love that says, “There darling. Mummy’s changed your nappy and fed you the bottle, and now I’m going out to visit friends. After all, mummy is an individual, and needs her drinkee with pals.”

Personally, having been born prematurely and helped to survive, I question whether my grandmother did me a favour. I know all that stuff about life is what you make it despite handicaps. I know it and I practice it. But it still doesn’t take away the fact I have lived with an almost constant sense of struggle that started in those first weeks of my life when I was struggling to survive. It’s a hell of a thing to feel that I have never caught up. It never happened in childhood, and it never happened in adulthood.

I can’t deal with this!

Being positive doesn’t take away the fact that my mouth never had time to develop properly, so my teeth are badly overcrowded in an extraordinarily narrow palate. It hasn’t stopped me feeling as if energy is like having a bank balance that keeps slipping into the red, and has to be carefully nursed to climb into the black again. Low energy reserves play havoc with your sex life. It made me resentful that on the one hand I had the urge, and on the other if I allowed it I was exhausted to the point of despair, often leading to infection. (3)

Being premature led me to become an introvert, always trying to find the heaven of the womb again to make up for feeling I had been pushed out before my time. I told this to a woman recently and she said “For goodness sake. Every man is trying to get back into the womb.” She was referring to the desire for sex, and that isn’t what I mean. I mean withdrawal. I mean the desire to fade back into the background of things where one no longer exists as an individual. I mean longing for death. And again, I am not talking about being suicidal. The drive to suicide is something else. I have been there a couple of times and it is different. What I am describing isn’t that. It is the hope, the longing, to go home again to the place where you can abandon all effort, abandon oneself – die.

I have actually been there a few times, so I know the place, or the state well. When it happens ones breathing stops spontaneously and you simply exist, all thinking and self melts away. It is a wonderful place to be, and makes me wonder if this is what yogis and fakirs aim at when they do their extraordinary breath holding practices.

So I writhe when I read about or hear about doctors and parents keeping wildly premature babies alive by all sorts of artificial means. I personally feel it is deeply cruel. For a start the baby needs enormous physical and emotional contact, yet is shut off in an incubator. Secondly, if my own experience is any measure, the sense of being unfit to meet external life is a burden to carry, and can last a lifetime. I was only eight weeks premature, and some of the premature babies kept alive today far exceed that. My love and compassion goes out to them. It goes out to you if you were born prematurely. We probably share similar pains and pleasures. So my love leads me to say to doctors and parents who are dealing with the issue of prematurity – please, please consider very carefully what your motives are for keeping alive such vulnerable little beings. Have some pity.

As a baby I was never an individual until I ripped my emotions apart from my mother through the repeated pain she gave me. I never wanted a life apart from her. I was in love with her with the most passionate and demanding feelings known. The baby expects this same ardour from its mother, this same desire to be continually in each other’s presence. The Oriental women and primitives have got it right when they carry their babies about on their back continuously until there is a natural development in the child to start exploring its environment.

As the baby I also need to be part of a group who wants me and gives me a name, and recognises my character, permitting it to flower. As a baby I am the great primitive. I am not a digitised recording of life. I am life, and I grow from old roots. Plant me in rich soil where women have tits filled with milk they want to share, and who love holding babies in skin to skin contact. Let me grow where people recognise that humans are part of the natural world in which reproduction, parenting, and mutual caring are the most important facts of life. Please don’t plant the seed of me in an industrialised culture in which women have to grab at machines and offices separated from their babies. Please don’t grow me stunted like that again. This time was too much. See page on Tony’s Other Personal Articles; LifeStream.

NOTES

(1) See the argument put forward by Jim de Wit on page 70 of Gary Zukav’s book The Dancing Wu Li Masters – Rider, 1993. The book is a fascinating survey of quantum mechanics.

(2) Elisabeth Hallett writes – About a dozen years ago, I stumbled across a mystery. I was working on a book about the postpartum bonding time, gathering parents’ personal stories, when I was struck by an unexpected fact. Quite a few parents emphasized that their connection with their baby had begun long before the actual birth. They told of sensing contact and communication during pregnancy–and in some of the most spine-tingling accounts, even before conception itself. Contact Elisabeth at soultrek@montana.com

(3) Smaller babies age faster and, by their 60s, have a more papery skin, a weaker grip and a slower brain than their heavier counterparts, a study has found. Those of lighter weight at one year will also go on to have cloudier eye lenses – an early indication that cataracts may develop – and worse hearing than their heavier peers.

Researchers believe that such ageing is programmed into us in the womb by factors such as the mother’s nutrition or hormone levels. The findings come from studies of birth and growth records in ledgers put together from 1911 onwards by nurses in north Hertfordshire worried then about the high infant death rate.

Dr Avan Aihie Sayer, of the Medical Research Council’s Environmental Epidemiology unit, Southampton University, followed up 850 of these babies – now aged 64 to 74 – in seeking a connection between foetus growth and the ageing process. Her findings relate to babies within the normal size range when they were one – from 18lb to 26lb. Babies of 18lb at the age of 12 months were on average 26 per cent more deaf when they were older, and had 16 per cent more cloudy eye lenses and four per cent thinner skins than did people who had been 26lb when they were one.