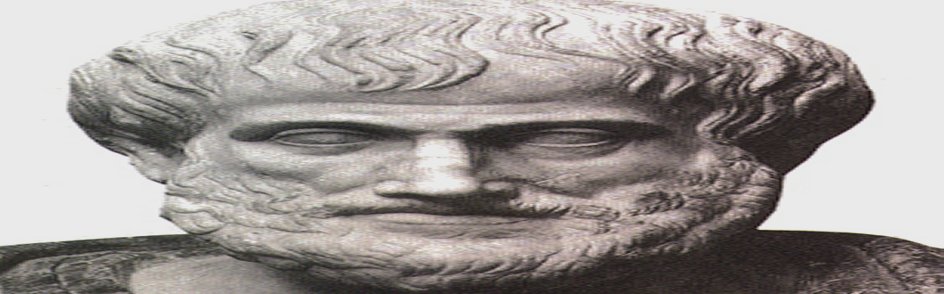

Aristotle on Dreams

Aristotle, a Greek born in the Ionian city of Stagira (384-322 B.C.) was one of the first writers to attempt a study of the mind and dreams in a systematic way. He was the son of Nicomachus the court physician to Amyntas III, king of Macydon. In 367 B.C. he went to Athens and studied at Plato’s Academy until Plato’s death in 347 B.C.. Along with Socrates and Plato, he became one of the great philosophers who were instrumental in forming the foundations of Western rational thinking.

Although in his early years Aristotle followed the Platonic belief that the soul and the body were separate entities, he later formulated the non-dualistic idea that the body and soul (soul in Greek thought was ones personal consciousness, personal memories and experiences) were polarities of one thing. In his treatise De Anima, part of his mature writings, he defines the soul as that which animates the body, that which quickens it to life. The soul is that which also directs the process of the body’s growth and survival. So the soul is the blueprint that directs the purpose of the material side of human nature. To quote from Search For The Soul (Time Life Books), ‘The oak tree is the purpose that the matter of the acorn serves.’

This concept, without of course detailed knowledge of DNA, is not unlike the present day view of the non dualistic view of body and mind, both linked not only to the blueprint from our genetic material, but also that our being is constantly a dynamic interrelationship between all parts.

Aristotle deals with the subtleties of sleep and dreams in three great treatises – De Somno et Vigilia; De Insomnis; and De Divinatione Per Somnum. (On Sleep and Dreams – On Sleeping and Waking – On Divination Through Sleep.) The views on dreaming are developed out of Aristotle’s concepts of mind and imagination, and his observation of how people deal with sleeping and waking. For instance he saw imagination as the result of sensory and subjective perception occurring after the disappearance of the sensed object. Recognising that the human mind can form powerful and realistic ‘afterimages’ of things no longer present. Aristotle carried this insight into the realm of sleep and applied it to dreaming. He added to this the observation that while awake we have the easy ability to distinguish between what is an external object and what is our imagined object. In sleep however this faculty disappears or is almost completely absent. This produces the sense of enormous reality we have in dreams, and the feeling that we are facing actual events and people. It is what Freud called the hallucinatory property of dreams. See: Freud; hallucinations and hallucinogens; hallucinations and visions.

Dreams were therefore, in Aristotle’s observations, not sent by a god – even animals could be seen to dream – but the product of experiences had while awake, and then used by our imagination during dreaming; or else arising from internal but perhaps subtle sensations such as the symptoms of illness. Because our ‘common sense’ faculty that usually distinguishes between fact and fancy is absent during sleep, we are thus prone to the amazing fantasies of dreams, beyond correction of our judgement or evaluation. However he does qualify this slightly by making one of the first historical references to the faculty of lucid dreaming, by saying, ‘often when one is asleep, there is something in consciousness which declares that what then presents itself is but a dream.’ Many authorities quote Aristotle as the first to mention lucidity in dreaming. However, this seems to be part of the mistaken Western sense of superiority. Buddhism, founded in 500 BC, had lucidity as part of its basic goals. Yoga, an even older practice, gave methods to wake up in sleep. See: Greece (ancient) dream beliefs – Buddhism and Dreams – Yoga and Dreams.

Useful Questions and Hints:

See Aristides.

Do I have a common sense attitude to dreams or am I lost in fantasy? If I have a common sense attitude to dreams, does my ‘common sense’ tend to kill out my creativeness?

Aristotle didn’t say much about altered states of consciousness – see ASC’s.